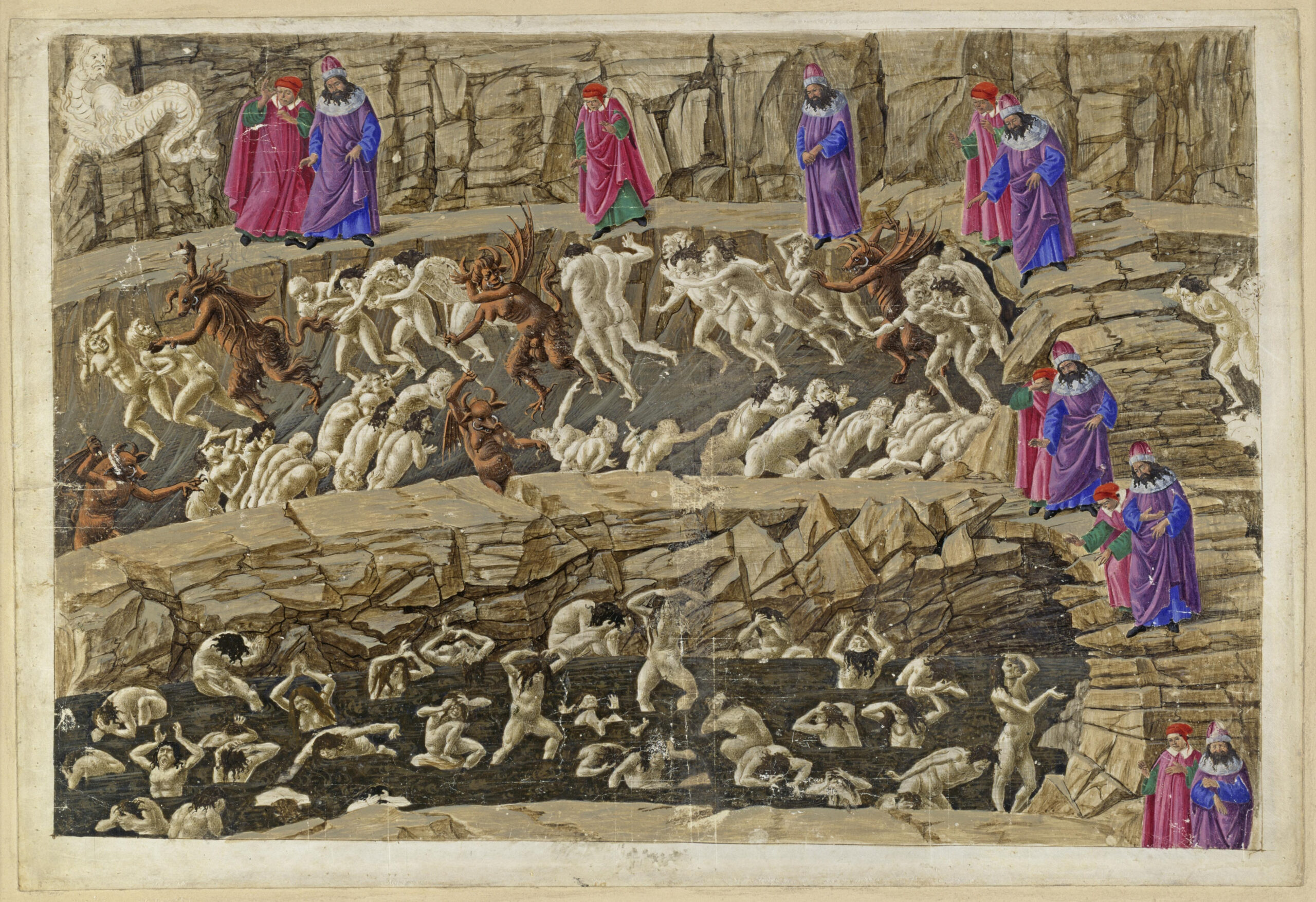

Although there were many Christians in Roman Africa, pagan manners and customs still survived in many of her cities. The people clung to their games in the circus, the cruel and bloody combats of the arena, which, though forbidden by Constantine, were still winked at by provincial governors. They scarcely pretended to believe in their religion, but they held to the old pagan festivals, which enabled them to enjoy themselves without restraint under pretense of honoring the gods. The paganism of the fourth century, with its motto, “Let us eat, drink, and be merry,” imposed no self-denial; it was therefore bound to be popular.

But unrestrained human nature is a dangerous thing. If men are content to live as the beasts that perish, they fall as far below their level as God meant them to rise above it—or rather, far further—and the Roman Empire was falling to pieces through its own corruption. In Africa the worship of the old Punic gods, to whom living children used to be offered in sacrifice, still had its votaries, and priests of Saturn and Astarte, with their long hair and painted faces and scarlet robes, were still to be met dancing madly in procession through the streets of Carthage.

The various heretical sects had their preachers everywhere, proclaiming that there were much easier ways of serving Christ than that taught by the Catholic Church. It was hard for the Christian bishops to keep their flocks untainted, for there were enemies on every side. When Monica was twenty-two years old her parents gave her in marriage to a citizen of Tagaste called Patricius. He held a good position in the town, for he belonged to a family which, though poor, was noble. Monica knew little of her future husband, save that he was nearly twice her age and a pagan, but it was the custom for parents to arrange all such matters, and she had only to obey.

A little surprise was perhaps felt in Tagaste that such good Christians should choose a pagan husband for their beautiful daughter, but it was found impossible to shake their hopeful views for the future. When it was objected that Patricius was well known for his violent temper even among his own associates, they answered that he would learn gentleness when he became a Christian. That things might go hard with their daughter in the meantime they did not seem to foresee.

Monica took her new trouble where she had been used to take the old. Kneeling in her favorite corner in the church, she asked help and counsel of the Friend who never fails. She had had her girlish ideals of love and marriage. She had dreamed of a strong arm on which she could lean, of a heart and soul that would be at one with her in all that was most dear, of two lives spent together in God’s love and service. And now it seemed that it was she who would have to be strong for both; to strive and to suffer to bring her husband’s soul out of darkness into the light of truth. Would she succeed? And if not, what would be that married life which lay before her? She did not dare to think. She must not fail—and yet . . . “Thou in me, O Lord,” she prayed again and again through her tears.

It was late when she made her way homeward, and that night, kneeling at her bedside, she laid the ideals of her girlhood at the feet of Him who lets no sacrifice, however small, go unrewarded. She would be true to this new trust, she resolved, cost what it might. Things certainly did not promise well for the young bride’s happiness. Patricius lived with his mother, a woman of strong passions like himself, and devoted to her son. She was bitterly jealous of the young girl who had stolen his affections and she made up her mind to dislike her. The slaves of the household followed, of course, their mistress’s lead, and tried to please her by inventing stories against Monica. Patricius, who loved his young wife with the only kind of love of which he was capable, had nothing in common with her, and had no clue to her thoughts or actions. He had neither reverence nor respect for women—indeed, most of the women of his acquaintance were deserving of neither—and he had chosen Monica for her beauty, much as he would have chosen a horse or a dog.

He thought her ways and ideas extraordinary. She took as kindly an interest in the slaves as if they had been of her own flesh and blood, and would even intercede to spare them a beating. She liked the poor, and would gather these dirty and unpleasant people about her, going even so far as to wash and dress their sores. Patricius did not share her attraction and objected strongly to such proceedings, but Monica pleaded so humbly and sweetly that he gave way and let her do what seemed to cause her so much pleasure.

There was “no accounting for tastes,” he remarked. She would spend hours in the church praying, with her great eyes fixed on the altar. True, she was never there at any time when she was likely to be missed by her husband, and never was she so full of tender affection for him as when she came home; but still, it was a strange way of spending one’s time. There was something about Monica, it is true, that was altogether unlike any other inmate of the house, as she went about her daily duties, always watching for the chance of doing a kind action.

When Patricius was in one of his violent tempers, shouting, abusing and even striking everybody who came in his way, she would look at him with gentle eyes that showed neither fear nor anger. She never answered sharply, even though his rude words wounded her cruelly. He had once raised his hand to strike her, but he had not dared; something—he did not know what—withheld him. Later, when his anger had subsided, and he was perhaps a little ashamed of his violence, she would meet him with an affectionate smile, forgiving and forgetting all. Only if he spoke himself, and, touched at her generous forbearance, tried shamefacedly to make amends for his treatment of her, would she gently explain her conduct. More often she said nothing, knowing that actions speak more loudly than words. As her greatest biographer says of her: “She spoke little, preached not at all, loved much and prayed unceasingly.”

When the young wives of her acquaintance, married like herself to pagan husbands, complained of the insults and even blows which they had to bear, she would ask them laughingly, “Are you sure your own tongue is not to blame?” And then with ready sympathy she would do all she could to help and comfort and advise. They would ask her secret, for everyone knew that, in spite of the violence of Patricius’ temper, he treated her with something that almost approached respect. Then she would bid them be patient, and love and pray, and meet harshness with gentleness, and abuse with silence. And when they sometimes answered that it would seem weak to knock under in such a fashion, Monica would ask them if they thought it needed more strength to speak or to be silent when provoked, and which was easier, to smile or to sulk when insulted? Many homes were happier in consequence, for Monica had a particular gift for making peace and even as a child had settled the quarrels of her young companions to everybody’s satisfaction.

To the outside world Patricius’ young wife seemed contented and happy. She managed her affairs well, people said, and no one but God knew of the suffering that was her secret and His. Brought up in the peace and piety of a Christian family, she had had no idea of the miseries of paganism. Now she had ample opportunity to study the effects of unchecked selfishness and of uncontrolled passions; to see how low human nature, unrestrained by faith and love, could fall. Her mother-in-law treated her with suspicion and dislike, for the slaves, never weary of inventing fresh stories against her, misrepresented all her actions to their mistress. Monica did not seem to notice unkindness, repaying the many insults she received with little services tactfully rendered, but she felt it deeply. “They do not know,” she would say to herself, and pray for them all the more earnestly, offering her sufferings for these poor souls who were so far from the peace of Christ. How was the light to come to them if not through her? How could they learn to love Christ unless they learned to love His servants and to see Him in them? The revelation must come through her, if it was to come at all. “Thou in me, O Lord,” she would pray, and draw strength and courage at His feet for the daily suffering.

The heart of Patricius was like a neglected garden. Germs of generosity, of nobility, lay hidden under a rank growth of weeds that no one had ever taken any trouble to clear away. The habits of a lifetime held him captive. With Monica he was always at his best, but he grew weary of being at his best. It was so much easier to be at his worst. He gradually began to seek distractions among his old pagan companions in the old ignoble pleasures. The whole town began to talk of his neglect of his beautiful young wife. Monica suffered cruelly, but in silence. When he was at home, which was but seldom, she was serene and gentle as usual. She never reproached him, but treated him with the same tender deference as of old. Patricius felt the charm of her presence; all that was good in him responded; but evil habits had gone far to stifle the good, and his lower nature cried out for base enjoyments. He was not strong enough to break the chain which held him.

So Monica wept and prayed in secret, and God sent a ray of sunshine to brighten her sad life. Three children were born to her during the early years of her marriage. The name of Augustine, her eldest son, will be forever associated with that of his mother. Of the other two, Navigius and Perpetua his sister, we know little. Navigius, delicate in health, was of a gentle and pious nature. Both he and Perpetua married, but the latter entered a monastery after her husband’s death. With her younger children. Monica had no trouble; it was the eldest, Augustine, who, after having been for so long the son of her sorrow and of her prayers, was destined to be at last her glory and her joy.

This article is taken from a chapter in Saint Monica by F.A. Forbes which is available from TAN Books.