A charitable young man, a former parishioner of mine, heard that I was stuck in quarantine. He texted me, indicating that he had just finished a weekend retreat, was in the neighborhood, and could drop off some victuals for his reclusive ex-pastor.

Not only was I moved by his kindness, I wanted to know more about his retreat. He was respectfully silent for a moment, and then thoughtfully said :

“There were good elements in the retreat, but disconcerting things, as well. We were told to sit in circles and share our woundedness, manifest our vulnerability. More than once, the soliloquies ended up blaming one’s father for his weakness or abuse. Once the guy had just unloaded what he had to say, the director would say, ‘OK, who’s next?’ It seemed disrespectful. I wasn’t interested.”

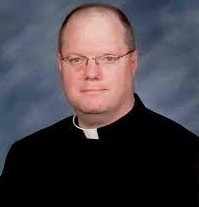

An entire generation of Catholics has been raised on this form of “retreat” in which, instead of considering the Last Things to better conform oneself to the will of God in order to make it to Heaven and avoid Hell, we’re invited to analyze ourselves, make an extra-sacramental confession in a semi-public forum and… “OK, who’s next?” I’ll leave the argument for the superiority of the retreat model made up of adoration, meditation, and silent recollection along with a spiritual director and confessor for another time.

Further, how we got to this notion of subjectivist retreat could be the basis for another article.

Similarly, about 12 years ago I was asked by a women’s group to give them a talk about my conversion. My first reaction was to consider it rather presumptuous on my part to think of my conversion as something already accomplished. My exterior reaction, however, left them non-plussed:

“I was ordained to bring souls to Christ and to Heaven. That includes preaching Jesus Christ, not speaking about myself. Further, neither you nor I have a claim on my interior life. It doesn’t belong to me and it’s not mine to set out for public consumption.”

Although those women were not interested in hearing the reasoning behind my position, it became the subject for my conversation with the young man mentioned above.

My benefactor, although raised on that style of “retreat”, intuited that something was wrong: it’s disrespectful. Spot on. But in more ways than one.

It’s disrespectful to God, others, and ourselves.

Homer’s notion of piety (eusebeia) preceded Aquinas’s (pietas) by 2,000 years. We live as social beings owing respect to others according to the nature of our relationship with them: God, parents, country, and indeed all others, whether above us or below us in social station. This is all in the order of justice. For Homer the worst sin possible was the sin against piety. Although Aquinas wouldn’t agree with that statement, Homer was on to something. His grasp of natural law, a sort of interior Mount Sinai, revealed to him the contents of the 10 Commandments. Speaking about the deficiencies of one’s father, as recounted above, goes against the 4th commandment and Homer would locate a rather low and brutal rung of hades reserved for such as that.

The rather recent practice in Catholic circles to speak about one’s conversion is loaded down with all sorts of spiritual ills. The virtue of modesty and decorum aims to protect us from effects of such indiscretion. Just as married couples ought not discuss their conjugal relations with others, so too, the Christian ought not immodestly discuss the intimate action of the Divine Spouse in one’s soul.

Already in the 5th Century, the great spiritual writer Diadochus of Photike warns us against speaking about our spiritual experiences:

“As when the doors of the baths are left open it causes the heat to escape from inside, so too, when a soul wants to speak much, even though all that he has to say is good, it dissipates the memory through the door of the voice. Thus deprived of opportune thoughts he unloads his indiscreet considerations on the first person he runs in to, because he no longer has the Holy Spirit who protects his thoughts from fantasy. For the good always shuns verbosity since it is at odds with every sort of disorder and fantasy. Therefore opportune silence is good and nothing else is the mother of the wisest thoughts” (Following the Footsteps of the Invisible: The Complete Works of Diadochus of Photike; Cliff Ermatinger, trans.).

A century later and in the West, St. Gregory the Great writes in similar terms of the dangers of spiritual immodesty:

“But, on the other hand, those who spend time in much speaking are to be admonished that they vigilantly note from what a state of rectitude they fall away when they flow abroad in a multitude of words. For the human mind, after the manner of water, when closed in, is collected unto higher levels, in that it seeks again the height from which it descended; and, when let loose, it falls away in that it disperses itself unprofitably through the lowest places. For by as many superfluous words as it is dissipated from the censorship of its silence, by so many streams, as it were, is it drawn away out of itself. Whence also it is unable to return inwardly to knowledge of itself, because, being scattered by much speaking, it excludes itself from the secret place of inmost consideration. But it uncovers its whole self to the wounds of the enemy who lies in want, because it surrounds itself with no defense of watchfulness. Hence it is written, As a city that lieth open and without environment of walls, so is a man that cannot keep in his spirit in speaking (Prov. xxv. 28). For, because it has not the wall of silence, the city of the mind lies open to the darts of the foe; and, when by words it casts itself out of itself, it shews itself exposed to the adversary. And he overcomes it with so much the less labour as with the more labour the mind itself, which is conquered, fights against itself by much speaking” (The Pastoral Rule, Bk III, Chapt. 14; Phillip Schaff, trans.).

In his usual, measured way, St. Gregory says that we may discuss vicissitudes we’ve experienced at the hands of another, but with the perpetrator involved, not with others. This, he claims, is meant to be medicinal for both. Of course, both Gregory and Diadochus make mention of the role of a spiritual father when discussing the action of grace. So, we’re not supposed to bottle everything up.

When well-meaning Catholic speakers recount their past sinfulness and sing the glories of God’s grace, it might be very gratifying to hear them, even as we praise God for His Mercy that endures forever but we ought to take heed of these Church Fathers’ counsels and cautions. Note that we do not discount the veracity of what our Lord has done in these repentant souls. In fact, so it seems, this is exactly what Diadochus and Gregory are trying to protect. The original grace of conversion is not the issue, but rather the enduring effect of that grace seems to be endangered by immodestly exposing it to the public. Whereas Diadochus mentions the lessening of the workings of the Holy Spirit as a result of immodest speech, Gregory underlines the increased access to our interior that the devil enjoys as a result of this spiritual striptease. It makes sense.

There can be a subtle, and sometimes, not so subtle, self-satisfaction in recounting one’s own spiritual experience. Decent intentions can easily be mixed with a myriad of other immodest intentions. Aquinas alerts us to the penchant for singularity called admiratio – the infantile desire to be different and call attention to oneself. Spiritual pride can easily weasel its way into one’s multi-faceted and evolving intentionality. Vanity, self-satisfaction, one-upmanship, competition in the spiritual field… all of these things, once in the mix, vitiate the original working of the Holy Spirit. His work is not ours and certainly not ours to spoil. Injustice to the Holy Spirit is the result of such immodest speech. Once offended, He has every right to withdraw His grace.

On the other hand, as Gregory observes, the devil gains an access to our minds that he previously did not enjoy. How does this work? The memory is the devil’s playground. Having been sacramentally forgiven of our sins we are still tasked with making reparation (also the subject of an upcoming article). But that’s not all. Our memories have been wounded through our sinfulness and the re-appropriation of our sinful past through constantly bringing it up grants access to the evil one and can lessen or undo the healing of one’s memories.

How do we sin against piety with regard to ourselves?

Catholic existentialist philosopher Peter Wust provides us with some insights:

“Piety towards oneself surrounds the self like a delicate membrane, which must be kept safe from harm if we want to protect our souls from being laid open to great dangers.”

This piety is concerned with “values, which are, as it were, a heavenly trust within us which we are bound to defend whenever a hostile power threatens to profane them.” He goes on to say:

“Our soul in its ultimate depths is a secret, and this is the inner chamber of the soul which we are, up to a certain point, obliged to preserve religiously. Reverence for ourselves forbids us to unveil the sanctuary of our souls with a rash and impious hand, and to do so would be a real profanation and show an unforgivable lack of modesty.”

In other words, none of us belong to ourselves. We belong to Him. And His work in us is His. Our interior experience is a Holy of Holies into which we may not enter without a hidden and holy fear. It requires gravitas and reverence, attitudes that ought to orient our piety and modesty. And it is precisely these that would prevent us from throwing open the gates of our inner sanctuary for all to see.

As I mentioned to the women’s group, my interior doesn’t belong to me and isn’t mine to expose to lurid eyes of the curious. Each of us has been entrusted to ourselves, but we are works in the making from the studio of an eternal Master. It would be a shame to interrupt His workings through over-exposure.