By tradition going back to early Christian times, the Divine Office has been prayed by Roman Catholics, arranged in such a way that the whole course of the day and night are sanctified with prayers.

This recitation of the Office of the Church praises God without ceasing, in song and prayer, and it intercedes with Christ for the salvation of the world. For this reason it has also been called the “Liturgy of the Hours.”

For centuries lay Catholics have visited Benedictine monasteries across the world, participating in the recitation of the Office, fostering a unique relationship between man and God. In Benedictine communities the recitation of the Office is called the Opus Dei or “work of God.”

The recitation is a prayer or “work” that allows the Christian to think of God and to sing His praises. It is an act of sacrifice and revelation that directs the whole self, psyche and soma alike to God, inviting man to come closer to forgetting himself in this one particular form of the worship of God.

It has been described thus by the Benedictine theologian, Dom Hubert van Zeller:

“The Divine Office is at the same time the word of God for man and the work of man for God. It is God’s revelation of Himself in human accents; it is man’s debt repaid to Him in the medium of sacrifice” (The Holy Rule, p. 172).

The Divine Office is for All

The recitation of the Divine Office is of such importance that Roman Rite clerics in major orders are bound to pray it daily. This includes priests, deacons, monks, nuns, and many members of Institutes of Consecrated Life and of Societies of Apostolic Life according to their approved Constitutions.

Vatican II’s Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy has an entire chapter dedicated to the subject of the Office, seen in chapter 4 of Sacrosanctum Concilium. In the same document the Council admonishes not only clergy, but also the lay faithful, to also pray the hours of the Divine Office with the whole Church with this recommendation:

“And the laity, too, are encouraged to recite the Divine Office, either with the priests, or among themselves, or even individually” (Sacrosanctum Concilium, 100).

Following on this, the Code of Canon Law also encourages laity to participate in the recitation of the Office:

“Others also of Christ’s faithful [the laity] are earnestly invited, according to circumstances, to take part in the liturgy of the hours as an action of the Church” (Code of Canon Law, 1174).

This call to unceasing prayer for clergy, and lay people, too, when possible, is in response to St. Paul’s exhortation: “Pray without ceasing” (1The. 5:17). For only in the Lord can be given and received fruitfulness and increase. This is why the Apostles first said as an example for all, “We will devote ourselves to prayer…” (Acts 6:4).

Hence, all who perform the recitation of the Office perform a service in fulfilling a duty of the Church, praying together with the Church in unison.

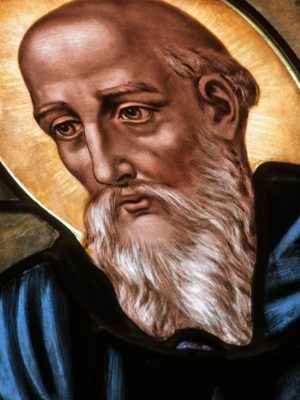

The Divine Office as a Gift from St. Benedict

St. Benedict in his sacred Rule (Regula), a book he wrote that is one of the most influential books in the history of Christendom, gives a significant amount of advice on the subject of the Office, its structure and the regulations he laid out for his followers.

This Rule, written in about the year 540, starts with a Prologue where St. Benedict speaks of his intention to create a “school” for the Lord’s service for those who have heard God’s call and followed Him.

All that follows in the Rule from hereafter is an elaboration of this theme of seeking God. A key component of the monastic vocation in light of this theme, as described by St. Benedict, is the recitation of the Divine Office said not alone, but in common.

The Rule with careful clarity gives detailed instructions of the order of Latin chants and prayers. More prayers were even assigned to the monks during winter months, taking into consideration the shorter length of day, assuming the monks would have slightly more time to pray while staying warm indoors.

St. Benedict explains in his own words the importance of the Office which revolved around seven daily services, also known as offices or hours. He writes:

“The prophet says, ‘Seven times a day have I praised you’ (Ps. 119:164). We will fulfil this sacred number seven if we perform the duties of our service at the hours of Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers and Compline, because it was with reference to these hours of the day that he said, ‘Seven times a day have I praised you.’ With regard to the night office the same prophet says, ‘In the middle of the night I rose to praise you’ (Ps. 119:62).” (The Rule of St. Benedict, Chapter 16).

St. Benedict devised that each of the hours of prayer were divided into a one-week Psalter. This allowed for all 150 Psalms to be said by the monks in one week, with the prayers divided into set times in the chapel, with an additional night office called Matins.

Benedict warns that such a life with regular hours to pray can be hard, particularly at first. He also acknowledged that problems could arise among the monks that may threaten to sabotage the practice, that was to be sung in unison by the monks in the chapel.

At the heart of Benedictine life is praying not only the choral Office but also the sung Conventual Mass, both celebrated in choir. Unfortunately, today not everyone follows all the chapters of the Rule, especially with regard to the structure of the sung Office in choir with its one-week psalter in Latin.

In the 1960’s the office of Prime was suppressed, and the Psalms were no longer distributed throughout one week, veering from the original approbations of St. Benedict. Some communities also gave up the beauty of chanting the Office in Latin, an immense cultural loss and deviation from what St. Benedict himself envisioned.

How to Say the Divine Office

The Mass and Office will always be at the center of Benedictine life.

The recitation of the Office by monks in a spirit of obedience and reverence has great merit. The act punctuates the day of the monk, like a leaven awakening the soul to sanctify the day as a gift of self to God.

Praying the Office worthily and embracing it sanctifies the whole life and assists the monk toward his goal of unceasing prayer – Ut in Omnibus Glorificetur Deus.

St. Benedict outlines the attitude of mind with which monks are to approach the duty of prayer. The saint’s aim was to get his monks to bring to their interior and exterior exercise a proper disposition of prayer that combined awe, simplicity, compunction, and purity of intention.

In heaven, St. Augustine teaches, satisfied love sings the hymn of praise in the plentitude of eternal enjoyment. Here below, yearning love seeks to express the ardor of its desires.

There is always need in spirituality for a holy fear and balanced reverence with yearning love. St. Gregory warned that irreverence is one of the signs of the soul’s deterioration, a sure sign that a monastic community is suffering.

St. Augustine sheds light on the subject:

“Let us then ever remember what the prophet says: ‘Serve the Lord in fear,’ and again, ‘Sing ye wisely,’ and ‘In the sight of the angels I will sing praises unto Thee.’ Therefore, let us consider how we ought to behave ourselves in the presence of God and of His angels, and so assist at the Divine Office that mind and voice be in harmony” (Sermons of St. Augustine, Sermon 255).

Here again, as in the exercise of humility, it is the omnipresence of God that inspires the monk as he recites the Office with proper reverence in a community setting. At the same time, it encourages him to keep up his unceasing struggle against distractions, boredom, against a sense of wasting time, and against the dismay that comes as a temptation to feel that no sensible progress is being made in the spiritual life.

In discovering the virtue of the Office, the soul discovers also the essential need to pray, and particularly the grace to pray throughout the day and night in sacrifice. Prayer and sacrifice are seen traditionally as the logical and necessary consequence of justice.

This is because God must be served for His great glory, thanked for His great glory, and atoned to for the outrages done to His glory.

Therefore, the Christian knowing about God’s existence and recognizing His sovereign rights over His creatures finds peace in expressing this knowledge and submission in the most immediate way possible through prayer.

Catholics will want to dedicate themselves in a special way to the expression of this attitude of prayer.

When appropriate, they will want to use their spiritual and physical faculties at the service of this expression, and they will know that in their exercise of praying the Divine Office a still more immediate and intimate relationship with God is being realized in response to St. Benedict’s admonition to pray in unison without ceasing.