How did Martin Luther come to believe in “faith without works?” Read the sad truth of this Augustinian monk and how he became repulsed by humanity’s wretchedness.

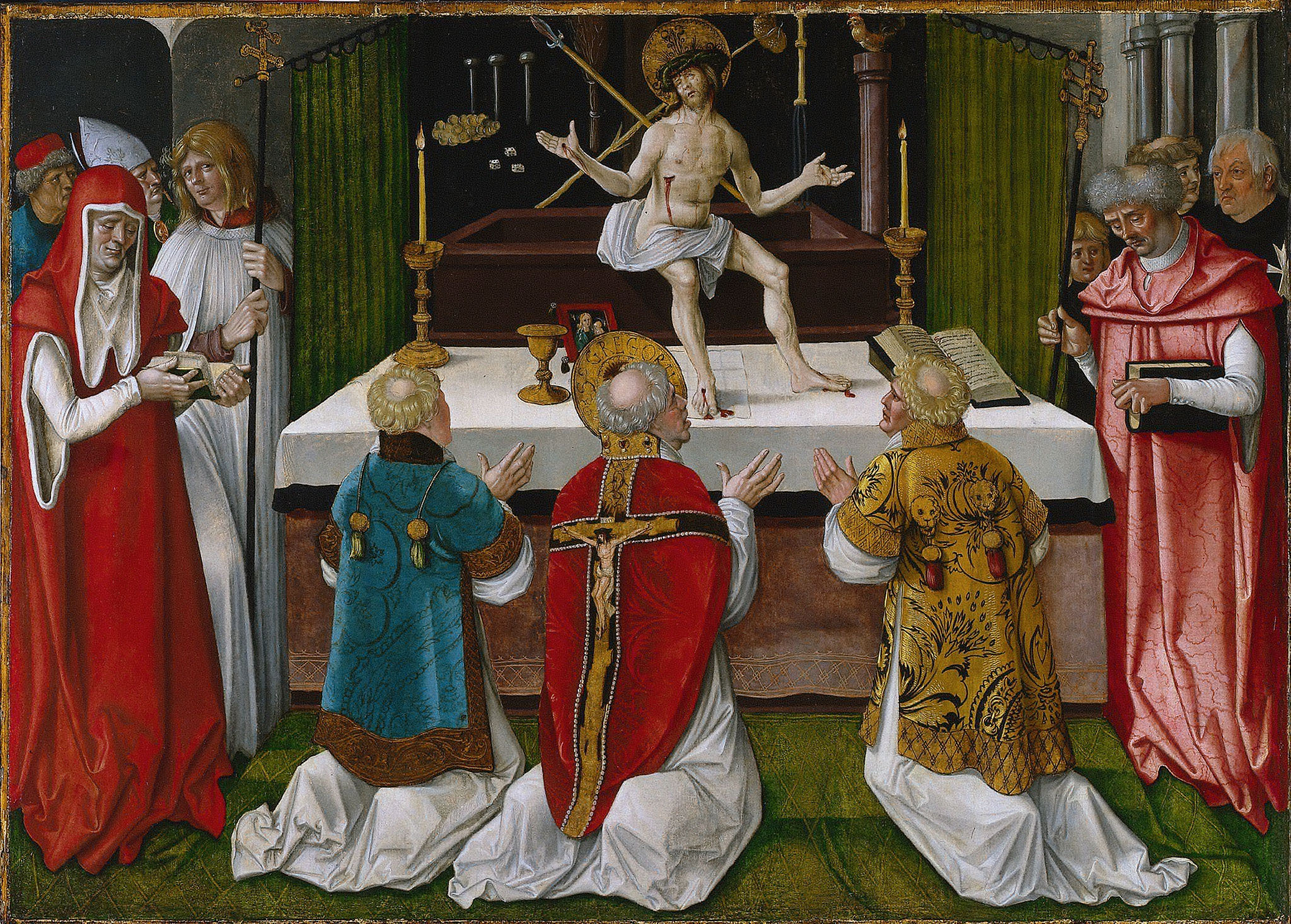

Luther thus began to establish an antithesis between faith and works. Faith, for Luther, was not assent to the truth revealed by God, but rather the sinner’s total act of trust in him despite his sinfulness. The Catholic Church had traditionally viewed God’s grace as operative through pious works. Luther saw God’s grace in opposition to man’s pious works.

Projecting his own personal inadequacies onto the human condition as such, Luther concluded that sin had so blinded man as to orient his nature fundamentally toward evil. This orientation necessarily destroyed man’s freedom, which meant that all man’s deeds, even pious ones, were merely extensions of his own corrupt nature and held no value in God’s sight whatsoever. For a person to think their good deeds could have any merit in God’s eyes was actually a grave sin.

With human nature completely in bondage to sin, man’s will enslaved, and even the best of his works no better than filthy rags, how could man possibly be saved? Here, Luther placed faith as an antidote to the false reliance on works. By an act of faith in Christ, the perfect merits of Christ become our own—not in the sense that Christ enables us to truly become righteous, but that his righteousness covers us like a cloak given to a beggar. It was a completely gratuitous act of God to which the sinner could not contribute in any way, neither by prayer nor by any pious deed whatsoever. All he could do was merely consent, and on that act of consent, all salvation depended.

Thus was the doctrine of justification by faith alone first conceived; it was conceived in opposition to what Luther believed was a slavish dependence on our own good deeds. The saddest thing about the story of Martin Luther is that he attributed his scrupulous condition to the Church’s teaching on good works, although ironically he was living in direct opposition to everything the Catholic tradition taught and his confessors advised.

Never had Catholic tradition taught that a man is saved by his own works; such was the heresy of Pelagianism, which the Church had soundly condemned in the fifth century. Neither Luther’s spiritual director nor any Catholic saint or authority had counseled any person to make their own sinfulness the fundamental reality in one’s relationship with God apart from the grace of Christ to remedy that sinfulness. “I can do all things in him who strengthens me” (Phil 4:13); this has been the dynamic truth in the heart of every Catholic saint since time immemorial. What Luther was rebelling against was not Catholic doctrine, but a convoluted caricature of Catholicism created by a tragic conflux of his own insecurities and his faulty view of God.

ooo

This article is taken from a chapter in Heroes and Heretics of the Reformation by Phillip Campbell which is available from TAN Books.