“Cantare amantis est (singing belongs to one who loves).”

—St. Augustine

It is a matter of fact that in the vast majority of Catholic parishes the liturgical music is abysmal. This is a decades-old dilemma that is still menacing the Church across the globe, the aftermath of the 1960s modernist purge that announced itself as a visitor from the future. Still, the Catholic impulse is to worship in harmony with a long tradition.

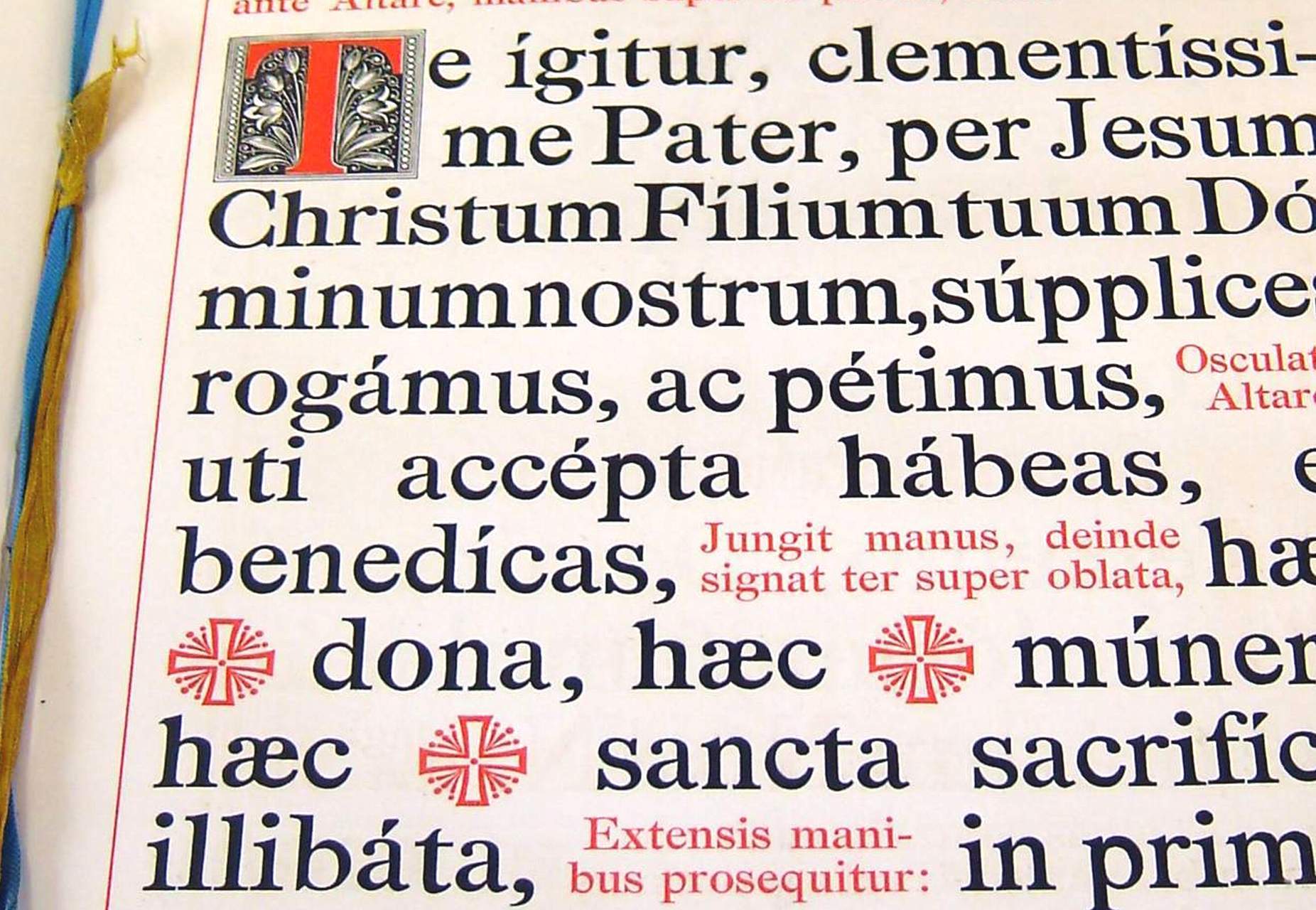

When the Church customarily speaks of its treasury of sacred music, it is referring to the Roman and universal heritage of the Latin rite. This is first and foremost Gregorian chant and its stylistic descendants. This also includes the tradition of sacred polyphony and sacred hymnody that is suited for the liturgy. This music is both artistic and sacred.

Chant and polyphony are considered the ideal of what constitutes sacred music in the Latin Church because they both perfectly participate in the general scope of the liturgy and contribute to the decorum and splendor of the liturgical ceremony. They clothe and add greater efficacy to the liturgical text; and they possess “the qualities proper to the liturgy, and in particular sanctity and goodness of form, which will spontaneously produce the final quality of universality” (Tra Le Sollecitudini, no. 1).

Meanwhile, there are some powerful voices in Church who outright deny there is an actual treasury of sacred music in the Roman rite. They emphasize that sacred music is part of a living tradition, which is true, but herein lies the clincher: they deny or ignore the preeminence of a codified repertoire of classical music (the treasury) that is to be performed over and over, belonging to the category of musical opus.

Liturgical music is of paramount importance because, to the utmost degree, it renders praise and thanksgiving to God while raising hearts and souls to the great privilege of offering the official worship of the Church, the ongoing reenactment of the holiest of acts: the supreme sacrifice of Christ on Calvary.

For this reason, sacred music in the liturgy, where the transcendent mysteries take place, must have a distinctive voice; it must be identifiably different and distinct from the rest of secular culture. Gregorian chant has been called a remedy for contemporary man’s search for meaning in music—soothing and stirring the human heart along with soul-piercing organ music. This is in strong contrast to folksy music commonly heard in most parishes.

The sad truth is that many progressive Catholic leaders have the upper hand, and their disdain for the mystical nature of the Church’s traditional hymnodies wins the hour. These shepherds choose to ignore or deny the treasury given to us from the wisdom of the centuries and the authority of the Church. They instead choose to lobby in favor of commonplace musical forms that, in their words, have “functional” and “dynamic” vision and “actuate active participation.” This is a tragedy as the liturgy itself demands the best possible presentation to convey its truth.

This is a sharp contrast to the mind of the Church, which has long held up the treasury of sacred music in such important documents as Pius X’s 1903 motu proprio Tra Le Sollecitudini, or Pope Pius XII’s 1947 Mediator Dei and 1955 Musicae Sacrae and even Benedict XIV’s 1749 Annus Qui Hunc.

This is not to say the Church is against contemporary liturgical music. Pius X, who sought to preserve chant and polyphonic offshoots, did not forbid modern compositions provided they are “of such excellence, sobriety, and gravity that they are in no way unworthy of the liturgical functions” (Tra Le Sollecitudini, no. 5).

Songs in their external forms heard in too many Catholic churches today undeniably lack excellence, sobriety, and gravity. How much of this music resembles a rock beat or could best be described as dribble? How much of it is from predominant musical forms that are based on popular and commercial stylings? Much of this music is not suited for the liturgy and it does not reflect early Church traditions. It is banal and sometimes even lacks proper theological underpinnings.

This is contrary to the Church’s constant tradition through the ages and it goes against the exhortations of the Roman Pontiffs. Pope John Paul II, at his general audience on February 26, 2003, reminded Catholics that “one must pray to God not only with theologically precise formulas, but also in a beautiful and dignified way.” The pope continued, clarifying his point when he said, “The Christian community must make an examination of conscience so that the beauty of music and song will return increasingly to the liturgy.”

Implicit in his remarks is the reality that the beauty of music and song has largely been abandoned and that this is a serious thing that demands an honest examination. At this late date, it can be said this sad reality prevails by inertia rather than by choice. There exists a state of ambivalence and apathy in the Church, and the will to make a change is missing.

The lack of understanding of what is meant by the Church’s treasury of sacred music runs deep. Understanding it properly—according to the mind of the Church—can dramatically and positively change and affect the life of a parish community. The process of leaning in favor of classical liturgical music and hiring professional musicians is rather uncomplicated and yields immense pastoral benefits. Raising the bar in favor of higher liturgical expression has a broad appeal; it is a universal concept.

Gregorian chant, a Latin-hymn repertoire, and sacred polyphony have proved enduring for so many centuries because of their universal message and reach. It is universal because it goes beyond the short reach of contemporary fashion and geography. Parish choirs and musical repertoire are in serious need of revival today if the Faith is to remain solvent. The music that inspired baby boomers no longer resonates with the young. This is because it had no universal message or reach. It was a contemporary local fad.

Classical, as a form of art, is regarded as representing an exemplary standard, traditional and long-established in form and style. The music of the Church’s treasury needs to be brought back for this very reason: it is great music and good for the Faith. This involves a continued process of reform. Lay involvement is essential because it is they who exercise influence over the parish liturgy. The leadership of the laity working with their pastor is the influential factor in the liturgical-musical life of the parish church. Yet the formation of the laity and many priests in this area is seriously lacking.

Musical values must be cultivated from the youngest age. A new process of understanding the merit of sacred music in the liturgy must be a necessary precondition for a classical education. Homeschool families will do well to teach their children the Church’s sacred treasury of music. This will provide the proper structure for future guidance and support for authentic liturgical renewal on the parish level.

While the Holy See and episcopal conferences and diocesan bishops hold the authority, it is important that an educated lay faithful exists and understands the difference between the sacred and profane, and how the believing community needs sacred (mystical) music. Much of the bureaucracy in the Church is unfocussed on this issue.

Christ is both God and man. Too much modern parish music reflects the humanity of Christ. But this leaves out His divinity. Lay people must be prepared for the task to learn more about sacred music and liturgical music because the two are not always the same. Not all sacred music is appropriate for the liturgical rites.

In conclusion, while the Latin Church is not limited to any particular style of music, a foundation remains in tradition and this allows for proper development. Tradition here is a delineation that indicates the exact position of the Church and portrays the wisdom of the centuries under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. For good or ill, music shapes the way people approach their faith, and we must return to our traditions or risk them being lost for yet another generation, un unspeakable loss.