St. Albert the Great Speculation: “What Color was Mary’s Hair?”

The desire to have a visual impression or image of any person whom we love is a very natural and human one. As beings who are both corporeal and spiritual, the affections of our heart and soul are inseparably conjoined to our physical senses. In the words of Saint Bonaventure, “the things in this perceived world signify the invisible things of God.” This is most supremely true of the person of Jesus Christ, who is the very incarnation of God. It is true also, to varying degrees and in varying modes, of all things in the created world, which each bear something of the vestiges of their Creator.

But, more than in any other created being, this is wonderfully realized in the Blessed Virgin Mary, who is justly described as “the immaculate mirror of the majesty of God, and the image of His goodness.” (Wisdom 7:26) In the words of Pope Blessed Pius IX: “Far above all the angels and all the saints, so wondrously did God endow [Mary] with the abundance of all heavenly gifts poured forth from the treasury of His divinity, that this glorious Mother, ever and absolutely free of all stain of sin, and perfectly fair and perfect, would possess the fullness of holy innocence and sanctity. Apart from God Himself, one cannot possibly imagine anything greater than her!”

It is only natural, therefore, that devotees of this most glorious Queen of the Heavens should seek to imagine her physical appearance. Indeed, this work of devout and pious imagination has produced innumerable artistic masterpieces depicting the Mother of God in a splendid variety of ways. Nevertheless, we read very little about the appearance of Mary in the theological literature, and relatively little even in devotional writing.

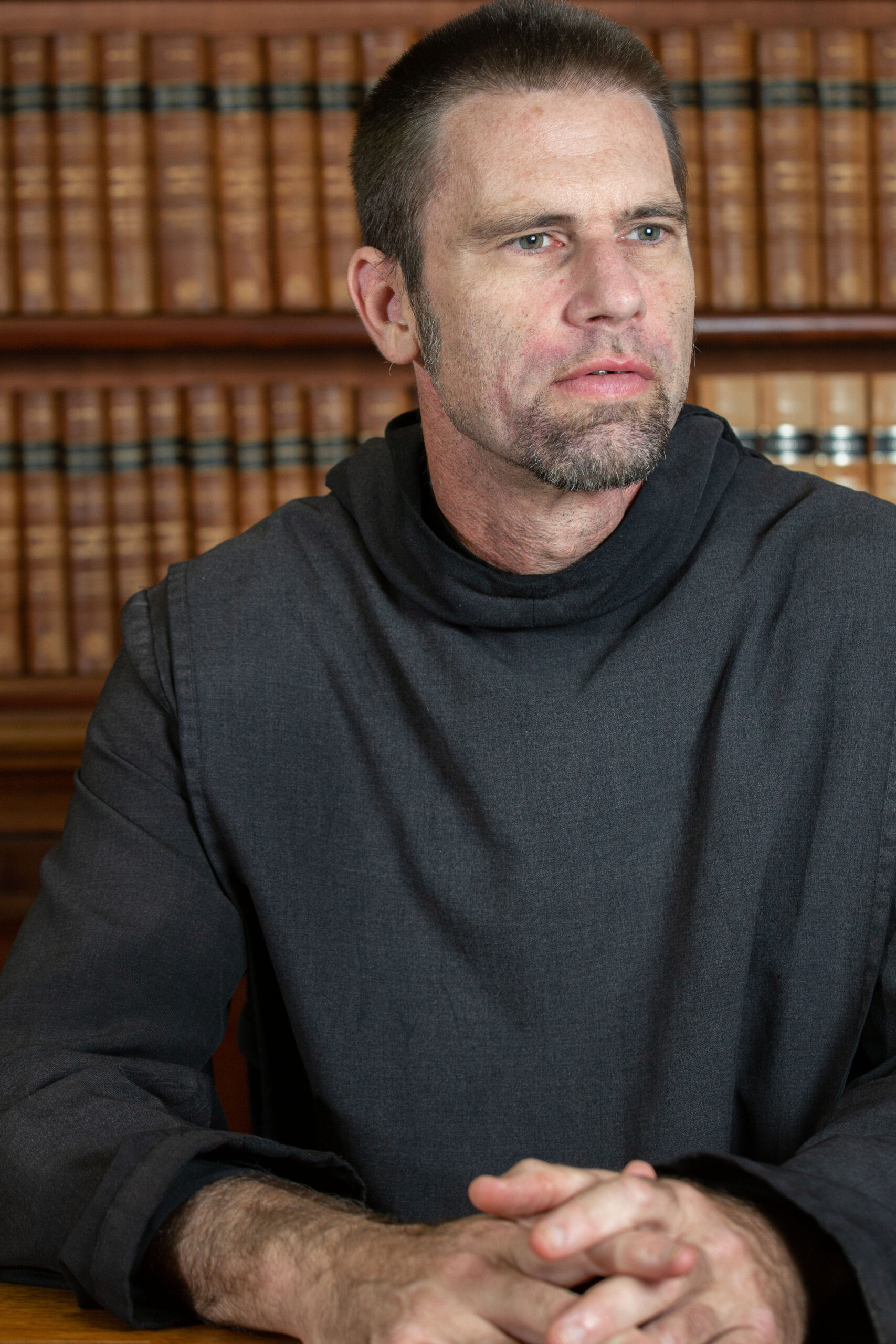

A noteworthy exception to this is in the writings of Saint Albert the Great (c. 1200-1280), known by the appellation of the Doctor Universalis (‘Universal Doctor’). Albert was a Dominican friar, who served as Archbishop of the German city of Regensberg. Reputed to be the most learned man of his time, one of Albert’s greatest distinctions is that he was the principal mentor of Saint Thomas Aquinas, the ‘Angelic Doctor’. Drawing upon his comprehensive knowledge of the physical and physiological theories of his time, as well as Scriptural and other evidence, in a number of instances in his vast corpus of writings, Albert sought to determine various questions about Mary’s physical beauty and appearance.

Given below is a translation of Albert’s discussion of the color of the hair of the Blessed Virgin, which appears as Question XVII in his magisterial work Quaestiones super “Missa Est.” Albert writes in a typical scholastic style, advancing various possible arguments and (where appropriate) their refutations, before formulating his own final conclusion. Of course, his opinions are necessarily conjectural, and based upon scientific concepts which are often no longer current. Nevertheless, his erudite speculations were inspired by, and are infused with, his own deep Marian devotion. Although his conclusions and reasoning certainly need not always be accepted, they do remain quite fascinating and persuasive. It must be admitted, of course, that some of the scientific theories cited by Albert will seem a little eccentric to the modern reader!

***

From Quaestiones super “Missa Est” by Saint Albert the Great

Question XVIII

Next, we may consider the color of Mary’s hair. According to medical authorities, there are four possible hair colors: black, reddish,[1] bluish gray,[2] and whitish grey.[3] Bluish gray hair results from a melancholic humor. Whitish grey occurs as a consequence of a deficiency of natural warmth and an excess of phlegm, and is most often found in the elderly. There can be no question of considering either of these two options in relation to the Virgin Mary—therefore, black and reddish remain the two possibilities which we must evaluate.

I. [First argument—based on the writings of Galen]

It seems that Mary’s hair would have been reddish. For redness attests to an abundance of healthy warm humors,[4] whereas blackness[5] can reflect inflamed warm humors and inflammation of the blood. Thus Galen[6] writes that ruddiness indicates a sanguine temperament, but blackness indicates either a choleric or melancholic temperament.[7] Since the sanguine temperament is more noble than either the choleric or melancholic temperament, it follows that the color which attests to the sanguine temperament is correspondingly more noble. Therefore, red hair would seem to be the most noble shade, and so the most fitting for Our Lady.

Galen also describes the body of a person in a condition of eucrasia,[8] saying: “An indication of optimum and perfectly balanced well-being is a mixture of redness and whiteness in the complexion,[9] and hair of a reddish yellow[10] color and slightly wavy.” Therefore, in a person in a state of optimum well-being [such as Mary], the hair should be of a reddish hue.

The same author says that in the head of a person of optimum well-being or eucrasia, there should be no kind of superfluity or excess in anything. Thus the mouth, ears, eyes and nostrils will all be of a moderate size, so that external forces, such as heat, cold, dryness, or dampness may not assail them excessively. For this same reason [of protection from the elements,] the hair on [many] young infants is found to be of a subdued reddish yellow shade.[11] Hence, on the ideal head of the person possessing perfectly balanced well-being, the hair also ought to be reddish. And since every aspect of Our Lady was certainly optimal, it logically follows that her hair should have been reddish.

II. [Second Argument—based on the writings of Constantine the African]

It seems that Mary’s hair would have been black. Constantine [the African][12] states that hair serves three principal purposes: it shields, protects and adorns the head. Hence it is that if a person lacks hair, it can be a source of embarrassment and consternation. This is especially so for women.

Now, as regards to the first two purposes, of shielding and protecting the head, it is evident that black hair is stronger, and therefore more effective, than reddish hair. Therefore, it follows that in the person of optimum well-being, the hair ought to be black, rather than reddish.

As regards to the other function of hair, namely adornment, it seems that the juxtaposition of two things which clearly contrast is more pleasing than the juxtaposition of two things which are of a somewhat similar, but not identical, color [and therefore neither properly contrast nor truly match.] If we assume [pursuant to Galen’s observation, quoted earlier] that Mary’s complexion consisted of a combination of whiteness and ruddiness, it seems that greater beauty would arise from her hair being black, rather than reddish, [since this would provide a contrast of the juxtaposed hues.]

It is to be noted also that a black color focuses the sense of vision more strongly than a reddish shade, which tends rather to scatter and disperse the attention of the vision. Reddishness is also an indicator of changeability and fluctuation, whereas blackness indicates firmness and stability, for it is the color associated with the element of earth.

The same Constantine, when he describes a body of optimal and ideal health, avers that a well-balanced body is neither excessively thin nor fat, and that its complexion is a medium balance between whiteness and redness. He says also that the hair is normally of a reddish-brown hue in infancy, but in childhood and youth typically darkens to black. Thus, according to the opinions of the illustrious physician Constantine [the African], black hair is a feature of a person in a state of eucrasia [such as Mary certainly was].

III. [Albert’s conclusions]

Now it should be noted that there is a very clear discrepancy between the opinion of Galen and that of Constantine. For Constantine asserts that a person with a perfectly balanced body will have black hair, while Galen believes that they will have reddish [or brown, or golden] hair. This contradiction is also to be found in many of those who write on physical beauty. For some assert: “If you wish to depict a beautiful woman, make her head like a globe, and her hair like golden rays of sunshine.” But others say: “[The ideal woman] is to be imagined with dark eyes, and with dark hair.”[13]

[As the matter cannot be settled by the citation of these authorities, it behooves us to turn to Scripture.] In the Song of Songs, in which spiritual beauty is represented by means of physical attractiveness, we read:

“Her hair, of deep and haunting charm,

Was like the leaf of some great palm;

And black as ravens’ gleaming plumes,

Or midnight roses’ sable blooms.”[14]

This verse, [which certainly pertains allegorically to Mary], seems to indicate that black hair was a feature of her exterior beauty, which manifested her interior and spiritual magnificence and purity.

Also, it is to be noted that the complexion of any individual is generally similar to that of their ancestors and relatives. Now, since Mary was born of the Jewish people and most Jewish people have black hair, it seems very probable that Mary likewise had black hair. Finally, Saint Veronica[15] testified that the hair and beard of Our Lord were black. Therefore, since a perfect physical similarity existed between Christ and His Mother, Our Lady’s hair must surely have been black.

[1] Rubeus. This evidently included all shades of red, brown, gold and blonde hair.

[2] Glaucus.

[3] Canities. Albert’s assertion that there are four possible colors of human hair (black, reddish/brown/golden, bluish gray, and whitish gray) will undoubtedly seem strange to most readers. It was, however, consistent with the classifications used at the time.

[4] The ‘humors’ were believed to be fluids in the body that affected a persons health and character.

[5] It is to be noted that Albert (and Galen) were not speaking of the differing complexions of various ethnic groups.

[6] A celebrated Greek physician of the 2nd century.

[7] This description reflects the beliefs in four particular types of temperament: sanguine (optimistic and bright) choleric (short-tempered and fiery), melancholic (introverted and pessimistic), and phlegmatic (calm and easy-going). These terms are sometimes used to describe different personality types, but they are no longer accepted as medical classifications.

[8] This term eucrasia and its cognates indicates a condition of a perfectly balanced body and temperament, which is both conducive of optimal health and aesthetically beautiful. Albert assumes that Mary, since she enjoyed the plenitude of grace, had this condition of eucrasia.

[9] It is to be noted that in making this statement, Galen was not speaking of differences in complexion relating to ethnicity.

[10] Fulvus.

[11] Subfulvus.

[12] Constantine of Africa was an 11th-century physician, of considerable reputation. He was born in Carthage in northern Africa, but moved to Italy and become a Benedictine monk at Monte Cassino.

[13] Albert does not identify these particular writers. The authorities cited were possible authors of treatises on artistic composition.

[14] See Song of Songs 5:11. This translation here is a free verse adaptation.

[15] Saint Veronica wiped the face of Jesus as He carried His cross way to Calvary. Albert does not identify his source for Veronica’s testimony on this subject.