“The only really effective apologia for Christianity comes down to two arguments, namely, the saints the Church has produced and the art which has grown in her womb.”

—Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

Catholics have long found solace in the contemplation of beauty. In fact, it could be said we mortals are dependent on beauty for life. Beauty is food for the soul, and we bathe in its glow. Of course beauty is reflected in different ways perceived by the human person.

Humans, with their intellect and will, experience beauty in nature that reflects the Creator. For Christians, the natural world is an object of contemplation that reveals the divine touch and presence of God.

In addition, the beauty of God is revealed through the lives of the saints and their life in the Church. The saints were close to God and resonate His life through their generous lives of selfless concern in action. The Christian soul is one whose moral beauty is perceivable, who is not just a moral agent but also a moral presence, marked by a life of virtue that shows itself to the contemplating gaze.

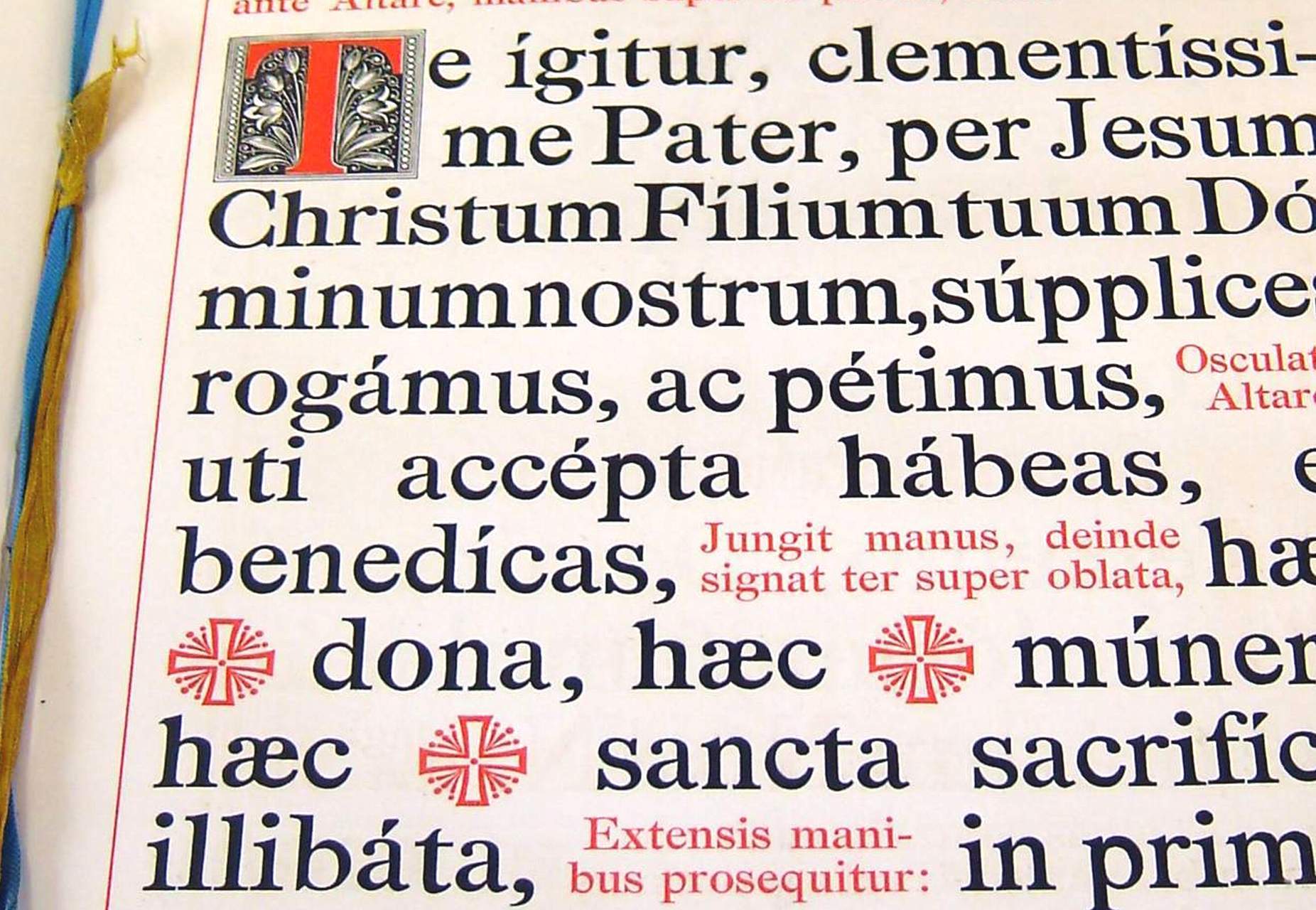

In the realm of art, beauty is an object of contemplation. There is beauty in works of art seen as the supreme artistic achievements of our churches and sacred liturgy—unparalleled in the world in the area of aesthetic value. They have a metaphysical resonance and ravish and inspire the soul. True art appeals to the imagination and invites the viewer to another place. Heavenly things are beheld and pondered in ecclesiastical art.

Beauty in church decoration and sacred music reflects the world as existing under the aspect of eternity. Arches and domes, steeples and stained glass all soar upward to heaven, reflecting a mystical connection with the world above. It demands wonder and reverence and fills the Catholic faithful with an untroubled and consoling delight that enraptures the Christian soul.

Beauty is tied to desire. It is a symbol of redemption, a signpost to the divine life. It places the transcendent subject before us and within the grasp of our hearts. It brings great satisfaction and ennobles the human experience.

Symmetry, unity, and form express a grandeur and other-worldly expansiveness. For Catholics, this is present in our lives through church architecture. It is a strong faculty that is directed toward the perfection of form and intricate harmony of detail, creating an order in our churches that reflects an order from heaven that lies deep in ourselves.

The inspiration for this beauty comes from ancient Rome and Greece, the pagan world of old, where great focus was put on a higher life. This led the pre-Christian inhabitants of Rome and Athens to turn their attention to the subject of higher beauty. Art and wisdom dominated their thinking. This concrete evidence from the ancient world shows that beauty, or the pursuit of it, has always been a human universal.

In the writings of Plato, it is asserted that all rational beings have the capacity to make aesthetic judgments. Further, the beautiful and sacred are connected in human emotions. The sense of beauty and reverence for the sacred are in tandem as proximate states of mind, giving an enhanced sense of belonging.

Even for the pagans of the ancient world, the reality of the sacred was to take them to the upper end of the beauty scale. Beauty was perceived as a matter of degree: the more beautiful the object, the more beauty was to inspire.

For the sacred today, beauty depends upon the prior conceptualization of the sacred object. At the same time, there are no greater tributes to human beauty than the medieval and Renaissance images of the Virgin and Child.

These tender images, as with all sacred images, are removed and held apart as untouchable. The experience of emotions when contemplating these great works of art have their parallels in the impact of satisfaction that beauty brings.

In the throw-away culture of today, there has been a flight from beauty. Beauty is today envisioned as a simple by-product of functionality. It is no longer the defining goal as it has been in previous centuries. Beautiful buildings get torn down. Churches are demolished, not even surviving on account of their charm. Function has become an independent variable at the expense of the beautiful. This reflects the unfortunate influence of Kant, who believed that aesthetic judgments are universal but subjective.

Beauty has been turned into a sense of “how nice!” or “I like this!” It contains a reassurance that the ego is right, a home where subjective reality finds confirmation. Art has become an enterprise through which the individual announces himself, doubting that beauty is attainable outside the human ego.

With impunity, popular culture has replaced art with a void of cultural relativism, since nothing is better than anything and all claims to aesthetic value are void. Modern society abounds in fantasy objects and the fulfilment of forbidden desires on screen where thought and feeling are purged of objective reality.

Modern art is better described as posturing. It justifies itself by announcing itself as a visitor from the future—a posture of transgression, holding up ugliness and shock value and downgrading beauty to the bottom because its true purpose is to challenge comforting illusions, a silly thing to begin with.

Despite the movement to spoil beauty, what about our higher aspirations? What about objective standards of beauty, values, and lasting monuments to the human spirit and to God? If Christians can grasp the emptiness of modern life, they can see art point to another way of being.

For Christians today, beauty matters and exists and the rational human mind can know it. The pursuit and love of true beauty is a signal to free ourselves from the sensory attachment to the ugliness that is propped up by the modern world of ideas.

The world’s conception of beauty does not attract contemplation but prompts desire. It is flesh animated without a soul. It is an eclipse of the soul by the body. The modern world denies the sacred and does not consider it has having parallels in the sense of beauty.

On the contrary, the experience of the sacred is a human universal. The sacred, like the beautiful, covers countless categories of object. The sacred is a reality, and we can know it. There are sacred rites, prayers, gestures, words, vestments, sanctuaries, and times.

Finally, what purpose does this beauty serve? Beauty and the sacred are adjacent to each other in our experience. The experience of beauty in art is connected with intention. Even the experience of natural beauty points in the direction of purpose.

True beauty has a goal for the understanding and passing on of eternal truths. Beauty invites us to focus on the individual object, as in sacred art, so as to relish the divine presence. Ultimately, this is why beauty matters. It leads us to God the author of all beauty.