As a new generation of Catholics is rediscovering the patrimony of Gregorian chant and realizing that it belongs to them in a specific way as part of their inheritance, they are flocking to the Latin Mass, with music as a major catalyst. Many are turning to Vatican Council II for guidance, which not only authorizes or recommends, but imposes Gregorian chant in the spirit of the liturgical action, “The Church acknowledges Gregorian chant as proper to the Roman liturgy: therefore, other things being equal, it should be given pride of place in liturgical services” (Sacrosanctum Concilium, 116).

In the years before Vatican II, the Catholic faithful were accustomed to having large choirs of parishioners well versed in the sacred chant. In an Apostolic Constitution prepared in 1928, Pope Pius XI urged the faithful to take an active part in divine worship by learning Gregorian chant so well that they could join in the singing during services, as formerly in the Church’s history was the custom everywhere. He suggested that churches, schools and associations could contribute greatly to this work. It is absolutely essential, he declared, that the faithful be not strangers or spectators, but, seized by the beauty of the Liturgy, they should take part in the ceremony, mingling their voices alternatively with that of the priest.

Monsignor Rudolf Bandas, who was an American peritus (theological expert) at Vatican II, had this to say on the subject of the supremacy of chant, “Gregorian Chant, in particular, is admirably adapted to express the thoughts and sentiments of the soul. Its varied tonality, its simple and majestic rhythm, its long and diversified neums, constitute a sort of a prolonged affective meditation which illuminates the divine truth and enkindles piety.”

He continued, “The liturgical chant of the Church diffuses charity and concord, and forms a bond of union between the faithful; for union of voices produces a union of hearts. And when the same melodies are chanted in the Universal Church there is formed an external brotherhood of men expressive of that corporate worship and internal unity which arise from our common membership in the Mystical Body of Christ.”

Finally, he concludes with a beautiful thought, “How inspiring it must have been to have heard the Psalms sung duly in majestic Gregorian strains under the vaults of those beautiful medieval cathedrals! The spirit of the Psalms and of Gregorian chant permeated medieval society and became the spirit of the times” (Religious Instruction and Education, pp. 78-79).

One author who has described poetically the exquisite beauties and qualities of Gregorian chant is the French writer Joris-Karl Huysmans. His 1895 novel En Route follows the story of the main character who is named Durtal, a thinly disguised portrait of the author himself. The book traces the conversion of this this character to Catholcism, an experience which reflects the author’s own personal journey. Durtal converts and ends up in a Trappist monastery, illustrating the progress of a soul surprised by the gift of grace. Meanwhile, all of this develops in a monastic atmosphere to the accompaniment of mystical literature and liturgy with Gregorian chant and beautiful art and architecture.

The melodies of Gregorian chant, in the author’s view, are in striking agreement with different styles of architecture. He writes, “It (Gregorian chant) also bends from time to time like the sombre Romanesque arcades, and rises, slowly and pensive, like complete vaulting. The De Profundis, for instance, curves in on itself like those great groins which forms the smoky skeleton of the bays; it is like them slow and dark, extends itself only in obscurity and moves only in the shadow of the crypts.” And at other times, the “Gregorian Chant seems to borrow from Gothic its flowery tendrils, its scattered pinnacles, its gauzy rolls, its tremendous lace, its trimming light and thin as the voices of children” (En Route, p. 6).

By way of summary he adds, “Born of the Church and bred up by her in the choir schools of the Middle Ages, plain chant is the aerial and mobile paraphrase of the immovable structure of the cathedrals; it is the immaterial and fluid interpretation of the canvases of the early painters; it is a winged translation, but also the strict and unbending stole of those Latin sequences, which the monks built up or hewed out in the cloisters in the far-off olden time” (En Route, p. 7).

In concluding, Gregorian chant awakens in the soul a longing for heavenly things. “Many a time,” writes Charles Warren Stoddard, an American author and editor known for his travel books, “did I listen to the music that was wafted from that beautiful church over the way. It was music unlike any I have ever heard – music that soothed and comforted me, yet at the same time filled me with an undefinable yearning” (White Harvest, p. 126).

Indeed, “Nothing,” says St. John Chrysostom, “so exalts the mind, and gives it as it were wings, so delivers it from the earth, and loosens it from the bonds of the body, so inspires it with the love of wisdom, and fills it with such disdain for the things of this life, as melody of the verses and the sweetness of holy song” (Expositio in Ps. XLI, in P.G., LX, 156).

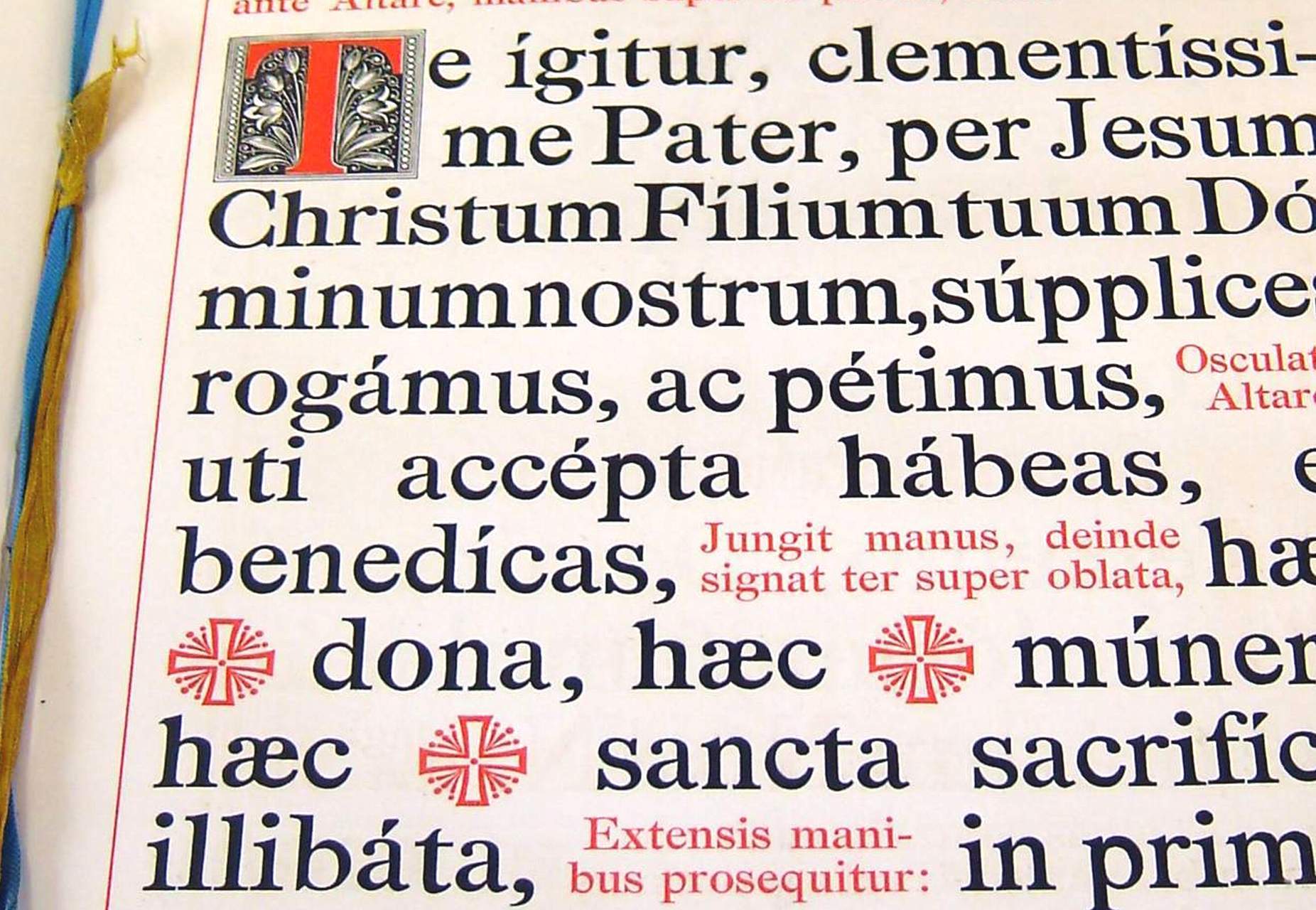

Finally, in his Motu Proprio known as Tra le Sollecitudini of November 22, 1903, Pope Pius X gave detailed regulations and guidelines for the performance of music in sacred liturgies. This helpful document still stands today as a guidepost to all Catholic parishes throughout the world. In it Pius X writes how Gregorian chant is an integral part of divine worship, and those who sing it have a true liturgical office. Though chant is not essential, it is nevertheless more than a mere accessory, for it “contributes to the decorum and the splendor of ecclesiastical ceremonies,” and “participates in the general scope of the Liturgy, which is the glory of God and the sanctification of the faithful.”

Pius X continues, “Gregorian chant has always been regarded as the supremodel for sacred music, so that it is fully legitimate to lay down the following rule: the more closely a composition for church approaches in its movement, inspiration and savor the Gregorian form, the more sacred and liturgical it becomes; and the more out of harmony it is with that supreme model, the less worthy it is of the temple.”

“The ancient traditional Gregorian chant must, therefore, in a large measure be restored to the functions of public worship, and the fact must be accepted by all that an ecclesiastical function loses none of its solemnity when accompanied by this music alone. Special efforts are to be made to restore the use of the Gregorian chant by the people, so that the faithful may again take a more active part in the ecclesiastical offices, as was the case in ancient times” (Tra le Sollecitudini, 3).