“For the Church, precisely because it embraces all nations and is destined to endure until the end of time…of its very nature requires a language which is universal, immutable, and non-vernacular.”

-Pope Pius XI (Officiorum Omnium, 1922)

At a time when old religious rituals are being embraced anew by many faiths, countless Catholics are choosing to pray again in Latin. While the vernacular has its obvious place in the prayer life of Catholics (in the Roman Liturgy it complements the Latin), this ancient language fills a need for transcendence, a reaching of the soul beyond the ordinary of life.

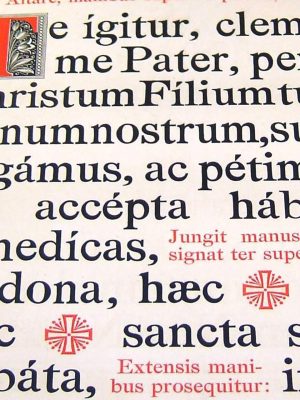

Latin is a delight to hear in the joyful groves of sacred liturgy, prayers, private devotions, sacred music, and academe. Nevertheless, it has become unintelligible to many Catholics, including clergy. For these Catholics, the Mass in Latin is often obscured by linguistic opacity, highlighting a failure of Catholic educators to hand on the rich patrimony of Latinity.

Latin fell on hard times in the turbulent culture storm of the 1960s. This is because Latin came to be seen as a thing of the past, an obstacle to progress and modernity. Today, a third generation of Latin illiterates is almost grown up. The hegemony of Latin illiteracy is corroborated by the sheer number of Catholic youth of all nations who show up to international gatherings of Catholics without any knowledge of Latin prayers; unable to make responses at Mass in Latin, unable to sing basic Latin hymns that are part of a common or universal patrimony that in past generations was taken wholly for granted.

Restoring That Which Has Been Forfeited

In view of the situation, one might be forgiven for imagining that some recent authoritative document banned any and all praying in Latin. No such document exists. In fact, the Church has always supported an enriched prayer life with the use of at least some Latin to cultivate the interior lives of both clergy, religious, and lay faithful alike. Knowledge of Latin therefore makes for an educated and informed Catholic population. Today concrete steps are being taken in many families to ensure the preservation of Latin studies and knowledge of basic prayers in Latin. This includes the passing on of how to follow Mass in Latin and how to make the responses with proper pronunciation.

Fortunately many homeschool moms are leading the charge. They are the new Spartans, who have taken on the responsibility to save Greece. In previous ages, Latin was preserved by the monks who were teachers. Today this role is being supplanted by moms with classical curricula who are changing a new “Dark Age” into a Catholic Renaissance. Thanks to this quest to instill a truly classical education in their children, Latin is being given a second chance with the token support it needs to be passed on to the next generation. Some would say this is the voice of the sensus fidelium at work.

Latin Reinforces Catholic Identity

Pope John Paul II clarified his own views on the fittingness of Latin in his 1980 letter to the Catholic world on the mystery and worship of the Eucharist. He wrote: “The Roman Church has special obligations towards Latin, the splendid language of ancient Rome, and she must manifest them whenever the occasion presents itself.”

Yet still so few definite steps to promote the use of more Latin, even in the Mass. The beauty of the Latin Mass that has been spread in recent years has by now been sufficiently demonstrated again and again which so many serious Catholics find so astonishingly moving and prayerful. Nor does one naively expect the use of Latin to solve all our problems; it is only a step, and even more must be done to make the liturgy and prayer life more meaningful and counter-cultural, with a keen sense of universality and mystery.

Secularism is today the omnipresent threat to Christian life and culture. The secularist influence is totalitarian. It would have the Christian faithful dichotomize their lives into this worldly-life, while pushing the mystery of spiritual language into irrelevancy. Unquestionably, the certain formality and apartness of Latin are a powerful fire-wall to combat the secularist reach. The use of Latin is well suited to public worship and Catholic identity. Latin puts due emphasis on the sacral character of the action of prayer – being set apart from the ordinary as something very different and ethereal. The use of Latin stresses “holy place” and “holy language.” Latin is an aid to the spiritual life, like other-worldly architecture, pews in a church, incense, and other sacred accoutrements. Too often the modern world disassociates the language of prayer with mystery.

Latin In Ages Past and Today

During the Renaissance and Baroque periods all educated men knew Latin. It was the bond of sages and savants throughout the West. With good reason it was seen as a unifying force, an iron symbol of continuity and unity. For centuries Latin Rite Catholics all over the world prayed together with the same words. Pilgrims could attend Mass in any place – including the Vatican – and they always found the exact same prayer formularies and responses in the same common tongue. There was a time when even eminent leaders of schisms and heresies knew Latin quite well, including Luther, Zwigli, Calvin, and Johannes Oecolampadius among other Reformers. There is even evidence that Christ spoke Latin during his lifetime in Palestine, hinted at in the Scriptures when he spoke directly with Pontius Pilate without an interpreter (John 18:33-38).

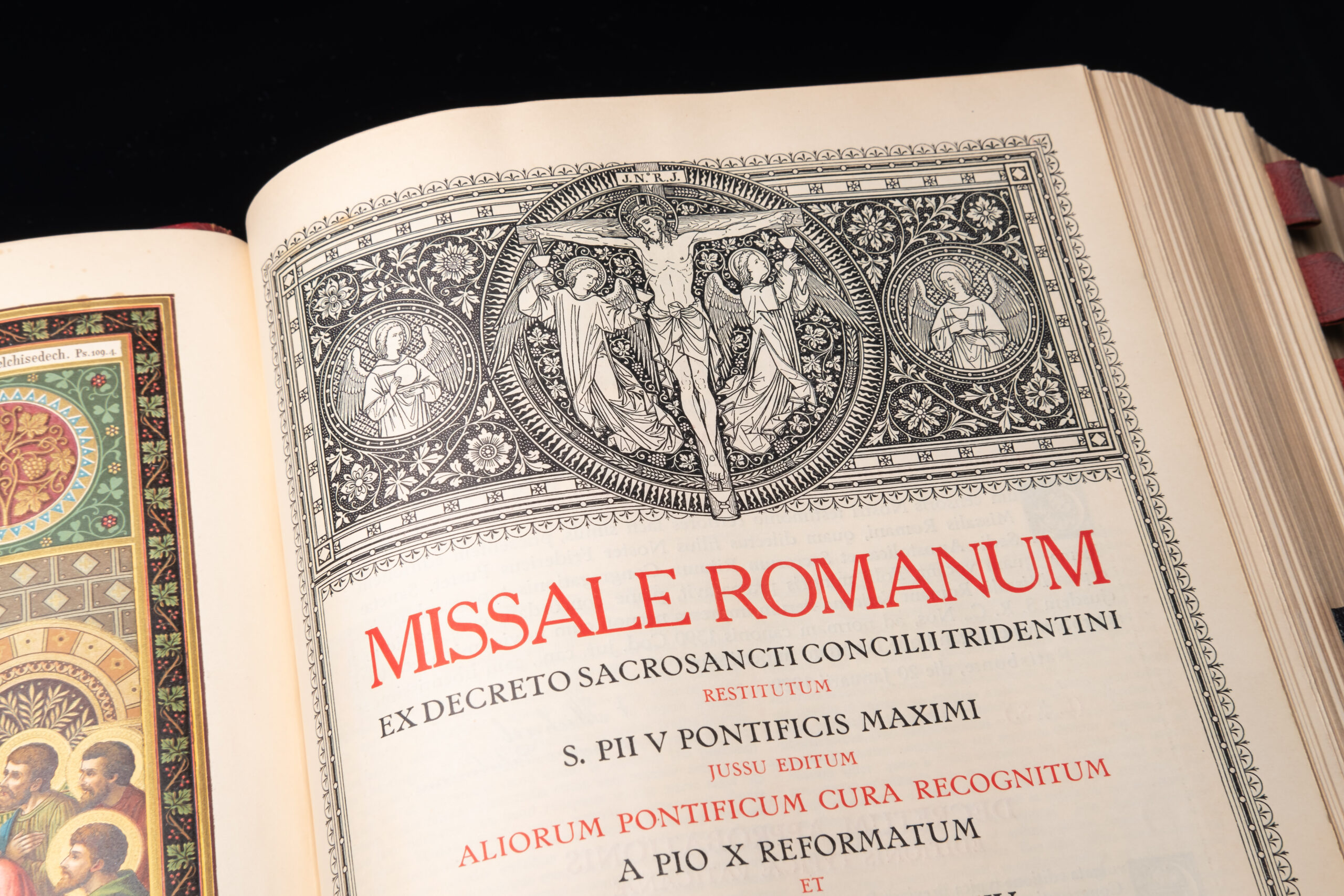

Since the legalization of Christianity in Rome, the Church gradually embraced Latin as is own language. This was due to a variety of reasons. With Mass and prayers in Latin – no nation need feel excluded. Official documents to bishops, encyclicals, general councils, all have effectively used Latin, making it irrefutably clear that the Church has given pride of place to Latin not only as a liturgical and musical language, but also as a working language to communicate her official documents. Because Latin is a dead language, the meanings of the words are settled and cannot change over time. The opposite is true with living languages, such as English.

Many Catholics today go shopping for their own spirituality. They are looking for more and Latin is what they find as they search for a deeper and more meaningful prayer experience. Also, for many, there is an intellectual satisfaction and consolation. Prayer speaks for itself. It holds its own sphere of time and space. It is not something ordinary – it is a sweet converse held between the soul and its Maker. It is an audience with royalty, a regal and mystical experience with God. It is necessarily suffused with correct teaching in unison with the universal Church. When Catholics pray in Latin they worship God according to the mind of the Church and over their own personal and cultural designing.

Preserving Latin in Prayer and Music

One of the precise functions of the language of prayer and liturgy is to draw men’s hearts to God for closer communion with Him. Words help to inspire, instruct, guide. The children of God need verbal expression that inspires and speaks to the soul. Many people complain their prayer lives are static. Maybe this is because the experience is too ordinary. One dynamism that comes into play is choice of language and its relation to mystery in music. In the words of Augustine: “He who sings, prays twice.”

Gregorian chant and sacred polyphony in Latin are sufficiently apart from modern secular music to make them totally imbibed with mystery and separate from secular culture. Latin hymns and chants are not jazzy and do not have a flippant slang of beats. Latin is a dignified language, the most perfect form of musical prayer, given to solemn prayerful utterances set to musical melody.

Many Catholics profess a personal fondness and preference for old Latin hymns. When done in English, chant never sounds as fully sonorous and resonant or as aesthetically delightful. Notoriously there is invariably some loss in translation. Those who know and love the older rhymes in the Latin texts of Gregorian chant often exclaim in horror as the ancient hymns are adapted to English. Today most professional musicologists are in almost universal agreement that no existing rhythmic interpretation in English of Gregorian chant, however devotional and aesthetic, can match the original Latin.

All over the world archaic languages are still used in religious rites and music. This is because people are rightly reluctant to make changes in the realm of the “sacral.” The archaic language is elevated and is a crucial link with the past. The use of an arcane liturgical tongue is a deliberate effort made to keep a sense of apartness and mystification.

No prejudice is intended to non-Latin brethren. In the Byzantine Rite, Old Slavonic has been used for centuries. In the Maronite Rite, Syriac is used, the spoken language of Christ. Indeed in the history of the Church the plebs sancta has always had recourse to a holy language, also in its music, that sets it apart. Even in the time of Christ, the Jews in the temple did not pray in their vernacular. Instead, they prayed in Hebrew, a liturgical tongue, reserved exclusively for divine worship.

Few languages are more monumental, lapidary, and dignified than Latin. With good reason the Church has always had an excessive preference for Latin in prayer and music. No translation can equal the majesty of the Creator Alme Sideum, the Dies Irae, or the Puer Natus Est Nobis. The loss of Latin music has therefore brought a major cultural deprivation.

Conclusion: Latin Has Always Been

The custom of praying in Latin has been a favored universal discipline of the Church that goes back to the paleo-Christian era. It is in the manner of the saints and our ancestors, and in the footprint of the time-honored liturgical traditions of the Roman Church.

All who have been privileged to visit Rome and pray in the Vatican, where the treasury of liturgical Latin has always flourished, are acutely aware of the thrill and sense of the universality of the Church and continuity with the past. Among some of the fondest memories of many travelers to Rome or Lourdes are hearing sung the Christus Vincit, or the Salve Regina, and being able to sing along. Visitors to a Papal Mass in Latin do not soon forget the matchless joy of celebrating Mass in St. Peter’s Basilica, surrounded by groups of fellow Catholics representing different continents and nations, all participating in the same spoken language of liturgy, a precious link joining time with time, space with space. As a symbol of unity, the experience is incomparable.

Lastly, praying in Latin is seen by some theologians over the centuries as being more efficacious. Satan hates Latin because it is a dead language, now used almost exclusively for the praise and worship of God in the Latin Church. It is a sacred tongue at the full-time service of divine worship in the Latin Rite. This immemorial usage has been confirmed by the Bishops of Rome, as the successors of St. Peter, who with clarity of teaching through the centuries have preserved and promoted the sacred treasury of Latin prayers and music for the next generation.

Readers are encouraged to pre-order a copy of Oremus: Latin Prayers for Young Catholics compiled by Katie Warner and illustrated by Meg Whalen (TAN Books, 2022). This wonderful new book for Catholic youth includes beloved prayers in English and Latin along with new renditions of beautiful artwork of the past. The expected release date is November 15, 2022.