Meeting Sheen: Recovery and Reconciliation

In her June 1953 public testimony, Bella Dodd informed counselor Robert Kunzig and the congressmen on his committee, “I only got out of the Communist Party completely, emotionally, when I found my way back to my own church.”

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Bella’s life was in chaos—a battle-ground of devastation and wreckage. Inch by inch, she withdrew from the Communist Party and reached for something better, something higher. It was God who was reaching for her. “God extended His hand repeatedly to me,” she said later, “but so blind was I that I ignored Him and went on in the pattern of my own desperation, caring not whether I lived or died, afraid to face each coming day, with no will to strike back at those who struck or degraded me. My mind was unable to give me the answers. I was left adrift like a ship without a rudder.”

Instead, Bella first sought a hole “to crawl into.” She was a fugitive from the Party, and her soul a fugitive from God. She faced nervous exhaustion. She found herself “besmirched, smeared, and terrorized.” From 1948 to 1952, she was in a vacuum, her soul feeling as empty as her apartment: “In those days I moved from one hotel to another, from one furnished room to another because I lost my home in all this thing and I kept moving because, as I moved the same faces would appear. . . . How did I find my way back?”

In the fall of 1950, Bella went to Washington as a private attorney to argue an immigration appeal. While walking down Pennsylvania Avenue toward the Capitol, she ran into her old friend, Congressman Christopher McGrath, who represented her old East Bronx neighborhood. When they were inside his private office, he said abruptly: “You look harassed and disturbed, Bella. Isn’t there something I can do for you?” She had a lump in her throat.

McGrath asked her if she wanted FBI protection. Though afraid, she refused. “I don’t want any more police protection. I’ve got them following me all the time, I’m forced to change my room, my hotels, and so forth, and so on; it’s just not a good idea.” At this time, Bella was being followed by both the FBI and the KGB.

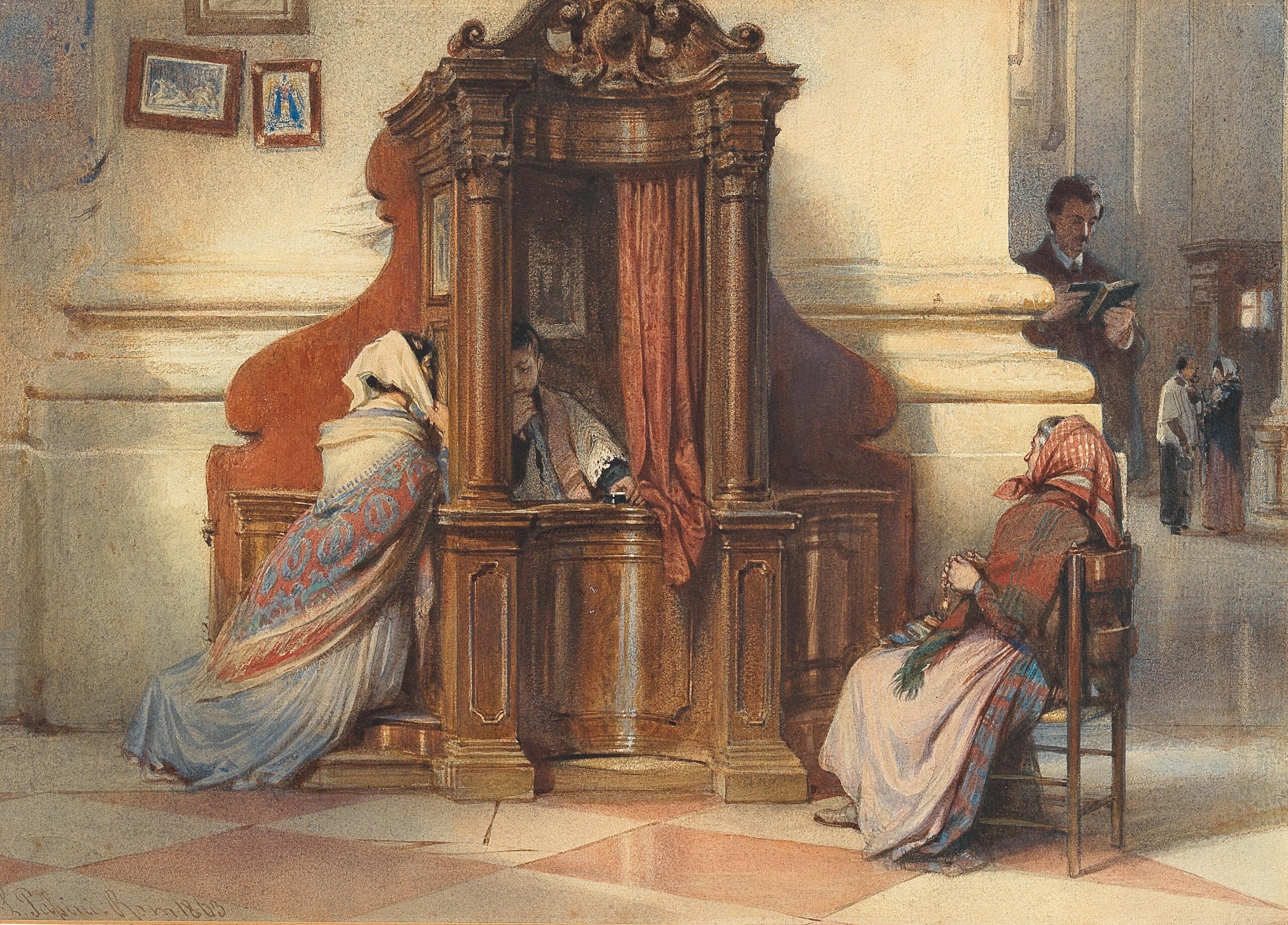

McGrath did not press the issue. Instead, he said, “I know you are facing danger, but if you won’t have protection, I can only pray for your safety.” Then he added, “Well, would you see a priest?” And suddenly within her, Bella shouted “Yes!” She feared, however, that she did not know what she would say to a priest.

The years of communist atheism had hardened Bella to that very prospect of talking to a priest, but now she felt it was something she could no longer resist. “Yes, I would,” she said with an intensity that surprised herself. McGrath responded: “Perhaps we can reach Monsignor Sheen at Catholic University.” Working with his secretary, Rose, McGrath arranged for Bella to meet Fulton Sheen.

Things were about to change, dramatically.

Meeting Sheen

Sheen agreed to see Bella that evening at his home in Chevy Chase. Only two years earlier, Sheen’s powerful book Communism and the Conscience of the West was published. It was as if Sheen had been studying Bella from afar. His writings on communism were second to none, especially among Catholics. And at last, Sheen would have the chance to meet a soul whose conversion he likely had been praying for and whose ideology was a clear threat to his flock.

On her way there, Bella already felt the “tiny flame of longing for faith within me.” It seemed to grow as she drove closer to Sheen.

Even then, she wanted to look for an “easy exit” as the famous priest walked into the room, “his silver cross gleaming, a warm smile in his eyes.” She said later, “He came out very much as he does on the television screen.”

It must have seemed intimidating at first, but her reservations quickly vanished as Sheen held out his hand: “Doctor, I’m glad you’ve come.” She would forever fondly remember those warm words. As she later recalled appreciatively, perhaps remembering how her communist “friends” would have received and berated her: “He didn’t say, ‘you old Bolshevik, you old bag.’ He said, ‘Doctor, I’m so glad you came.’” He then observed: “Dr. Dodd, you look unhappy.” She said: “Why do you say that?” Sheen replied: “Oh, I suppose, in some way, we priests are like doctors who can diagnose a patient by looking at him.”

She began to cry as he put his hand on her shoulder. He comforted her. Unlike the American Bolsheviks who descended on Bella in show trials without mercy, Fulton Sheen was all mercy. Bella recalled: “He kept saying, ‘There, there, it won’t be long now.’ . . . He only let me cry, and then, without realizing it, I found that we were both on our knees before the Blessed Mother in the little chapel.”

As the conversation seemed to slow to a halt, Sheen had led her gently into that small chapel, where both bowed before a statue of Our Lady. Like a little girl again, Maria Assunta Isabella felt a peace, stillness, calm.

This was certainly a turning point in the life of Bella Dodd. She was to remain deeply devoted to the Blessed Mother for the rest of her life and keep a statue of her in her office. Later, she could not recall how long she and Sheen had remained there, but “for the first time in my life, I knew peace, which I hadn’t known for many years. When I got up from my knees . . . my tears were dry.” Sheen then said to her: “Bella, if you want to protect the people whom you say that you love, the people of this country, and all the human beings of the world, then to do the right things, you must know something about Christianity. Your parents were peasants, but you, an educated woman, have to know.”

When they left the chapel, Sheen gave Dodd a rosary. “I will be going to New York next winter,” he told her. “Come to me and I’ll give you instructions in the Faith.” On her way to the airport, she marveled at “how much he understood.” With an unexpected sense of serenity, she held that rosary tightly all the way to New York and thereafter carried in her pocket always.

But Bella put off her visit to Monsignor Sheen. By winter, she had again retreated into darkness. She wandered into some New York City churches, which she said were the only places where the churning inside her stopped and where fear left her. She spent Christmas Eve with Clotilda and Jim McClure, who had previously lived at her house on Lexington Avenue. They read from the Bible, ate a simple supper, and then Jim walked her to the bus stop. She said she has no recollection of leaving the bus that evening, but she found herself in Saint Francis of Assisi Church on New York’s West Side. The choir sang Christmas hymns, and she realized that these were “the masses I had sought through the years, the people I loved and wanted to serve, people of all races and ages. Here was a brotherhood of man with meaning.”

The Midnight Mass was packed. She wedged her way in. She prayed over and over, “God help me. God help me.” When Mass ended, she walked the streets alone for hours, but she felt different; she felt a “warm glow of hope.” “I knew I was traveling closer and closer to home,” she wrote later, “guided by the Star.”

She was on a different walk now. She would never again return to the School of Darkness.

This article is taken from a chapter in The Devil and Bella Dodd by Mary A. Nicholas, MD and Paul Kengor, PhD which is available from TAN Books.