Growing up, I often saw my father reading a thick biography of Saint John Vianney. Some years later, I would pick up my own copy of The Curé D’Ars and read about the devil and John Vianney.

“For the space of some thirty-five years—from 1824 to 1858—the Curé d’Ars was subjected, even outwardly, to the molestations of the evil one,” says the biography. There were eerie noises by the curtains. There was snarling and the murmuring of incomprehensible voices. There was an invisible presence that would throw chairs, rocking the furniture.

There was the time when the devil so troubled Vianney that he asked the village’s wheelwright to keep a watch with him for signs of robbery. Trembling with a gun in his hands, listening to the violent shaking of the lock, the wheelwright felt the presbytery convulse, as from an earthquake, for a quarter of an hour. When Vianney asked him to keep watch a second night, the young man answered, “M. le Curé, I have had quite enough.”

There was the time when Vianney’s sleeping sister repeatedly heard a tremendous noise in the presbytery, like the sound of half a dozen men pummeling. Terrified, she ran to her brother in the church. “O my child! You should not have been frightened: it is the grappin,” Vianney said, referring to the devil. “He cannot hurt you: as for me, he torments me in sundry ways. At times he seizes me by the feet and drags me about the room. It is because I convert souls to the good God.”

Then there was the old saying, of mysterious origins, that the devil once confessed that if there were three men like Vianney in the world, the evil spirit’s kingdom would be broken.

Sometimes, I would think of that story, wondering how many John Vianneys it would take to curb the power of the devil today.

***

We live in a world as haunted as ever by demons. In his extraordinary book The Devil and Karl Marx,Paul Kengor describes a man fixated on those infernal powers—a man who spawned an ideology that Kengor likens to “an unclean spirit that should never have been let out of its pit.”

Born thirty-two years after Vianney the priest, Karl Marx wanted to be a poet. His verse was dark, stygian. In “The Player,” a violinist mad with “hellish vapors” cries, “See this sword? The Prince of Darkness sold it to me. . . . Ever more boldly I play the dance of death.” This player, says a biographer of Marx, “is clearly Lucifer or Mephistopheles, and what he is playing with such frenzy is the music which accompanies the end of the world.”

“My soul, once true to God, is chosen for Hell,” wrote Marx. He had once been described by Friedrich Engels as a presence that “leaps upon his prey”—“as though ten thousand devils had him by the hair.”

It is unsurprising, then, that the 1848 Communist Manifesto of Marx and Engels begins with the conjuring of an ominous spirit: “A specter is haunting Europe—the specter of Communism. All the powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this specter.” While Vianney was battling the devil from his quiet village in France, elsewhere in Europe something terrible was loosed.

Marx, Kengor says, “wanted to burn down the house.” Marx loved to quote Goethe’s Faust: “Everything that exists deserves to perish.” Marx was obsessed with the words “abolition” and “criticism”; he stood for the “abolition of private property,” the “abolition of the family,” the “abolition of religion,” and “the ruthless criticism of all that exists.”

This obsession with deconstruction marks the essence of Marx’s project—and makes it alarmingly protean, resilient. This “killer ideology,” says Kengor, left an estimated 140 million dead at the hands of communist governments in the twentieth century. But when Marxism mutated—when, as Kengor puts it, it “went cultural and sexual in the twentieth century”—it left a whole new trail of “cultural carnage,” “human wreckage,” and “soul damage.”

A “Frankenstein monster” was born when Marxism married Freudianism—and its name was cultural Marxism.

***

“These Marxists,” Kengor says of the cultural Marxists of the Frankfurt School, “were all about culture and sex. The Frankfurt school protégés were neo-Marxists, a new kind of twentieth-century communist less interested in the economic/class ideas of Marx than a remaking of society through the eradication of traditional norms and institutions.”

Kengor then relates the disturbing history of the Frankfurt figure popularly dubbed the “Father of the Sexual Revolution”—Wilhelm Reich. In his twisted autobiographical writings, Reich recalls everything from fantasies of incest with his mother to actual molestation of his farm animals. Reich crusaded for “the genital rights of children adolescents”—the “naturalness of genital self-gratification for the child.” As Kengor points out, Reich was “widely read by the 1960s New Left—the children of the sexual revolution.”

“The children of the 1960s would be [the Frankfurt School’s] twitching guinea pigs and guzzling alcoholics,” Kengor says. These disciples would be “intoxicated by lofty dreams (more like hallucinations and bad acid-trips) of fundamental transformation of the culture, country, and world. And a generation or two still later, they would become the nutty professors who mixed the Kool-Aid for the millennials who would merrily redefine everything from marriage to sexuality to gender.”

At one point, Kengor tells the story of Kate Millett, the Marxist-feminist author of Sexual Politics, the “Bible of Women’s Liberation.” Millett’s sister Mallory would hear from women about how Kate’s book “destroyed” their lives—about the children lost through abortions and the families shattered by motherly abandonment. Kate herself left her husband for a series of female lovers, legally married another woman, and, according to Mallory, wanted “the smashing of every taboo,” from promiscuity to witchcraft.

Mallory, for her part, would describe Kate as someone whose face would hauntingly take on “forms,” as if she had “something inside of her”—someone with “eyes rolling in her head” and “frothing at the mouth.”

***

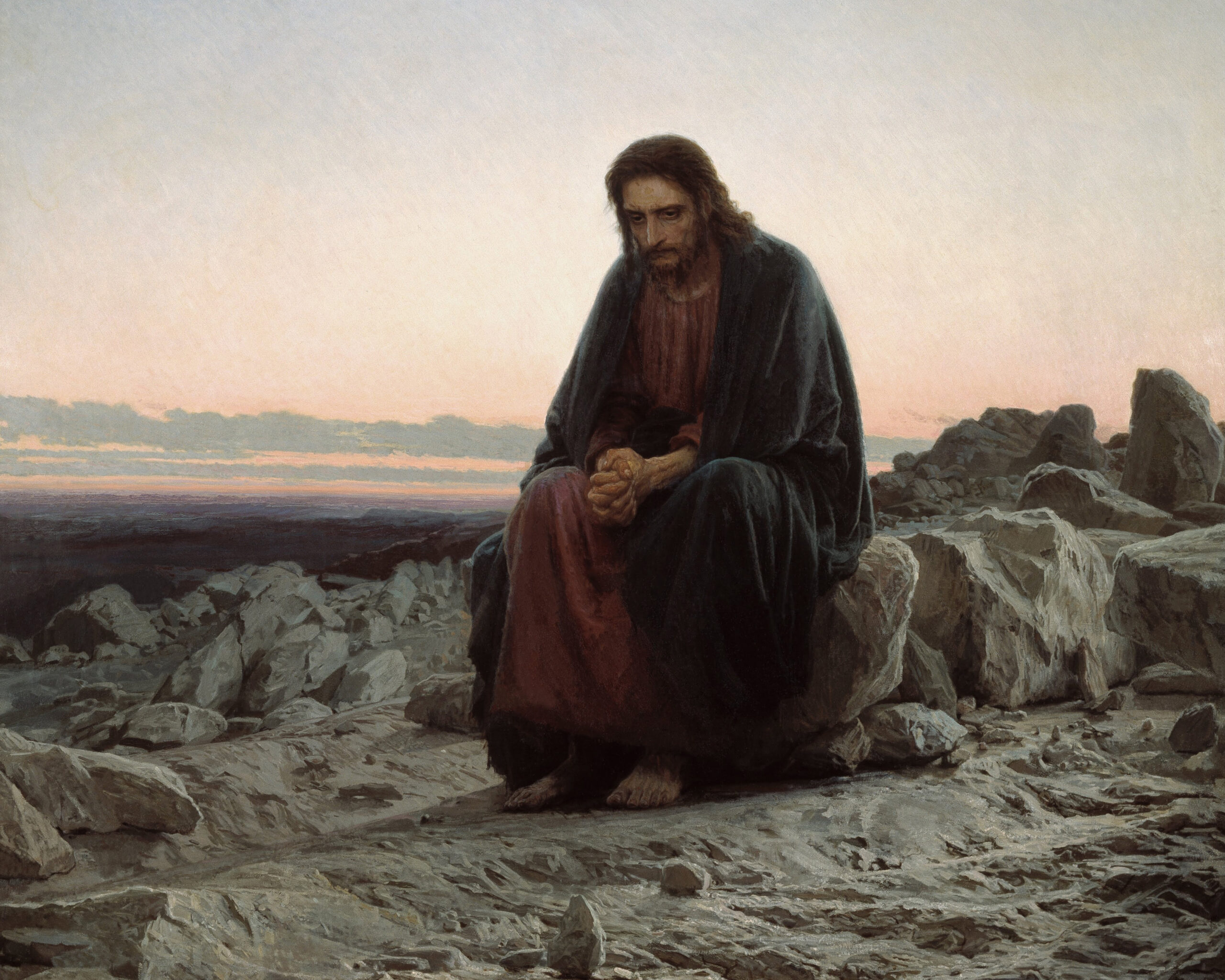

One day in 1850—two years after the release of the Communist Manifesto—a woman who had the marks of diabolical possession “leaped and danced and talked extravagantly” as a crowd gathered around her in France. Proceeding to tell the life of every soul present, she spied Vianney and cried, “As for you, I have nothing with which to reproach you.”

Then, as if suddenly grasping something damning, the woman told Vianney that he had once taken a single grape. When Vianney answered that he had once taken, and repaid, a grape while dying of thirst, the woman hissed that the owner never received the payment—trying to quibble over the sanctity of a man who fasted for days, spent nights in prayer and penance, and devoted up to sixteen hours a day to the confessional.

I don’t know how many John Vianneys we need, over 150 years later, to drive out the spirits of the devil and Marx. But I believe in the singular power of the saint’s intercession for a world as haunted as ours.

St. John Vianney, ora pro nobis.