The current battle playing out in the public eye between a Russian authoritarian leader and the people of the Ukraine is unfortunately nothing new. This is a rivalry that goes way back. And the worst times was the period when Ukraine was forcibly incorporated into the Soviet Union and its atheistic and (indeed) genuinely evil empire.

One of the ugliest manifestations of those Soviet evils came in the early 1930s. It was one of Joseph Stalin’s long line of crimes against humanity. In this case, it was Stalin’s horrendous forced collectivization of agriculture in the Ukraine, which led to the starvation of millions. A huge number of kulaks (land-owning and better off farmers) were uprooted and had their land stolen by the state or were themselves carted off to Siberia. Moreover, Stalin made it a criminal offense for anyone to publicly mention the disaster, punishable by prison.

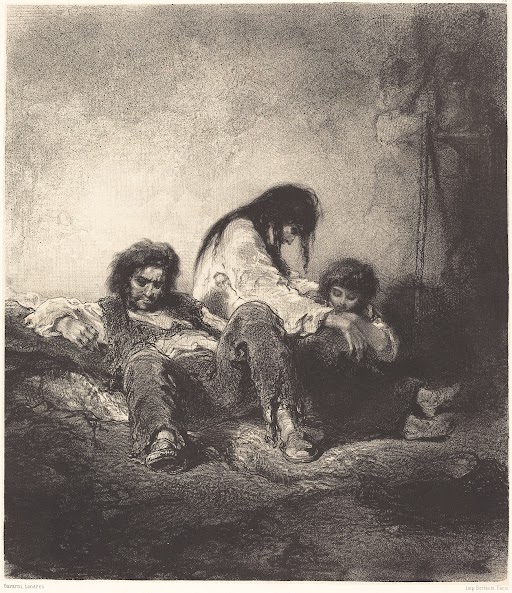

That particular crime against humanity is known in the Ukraine as Holodomor, a purposeful famine pursued by Stalin. This “man-made catastrophe,” as it has been rightly called, resulted in 5-10 million people starving to death. At one point in 1932-33, scholars estimate, some 30,000 people per day were perishing.

The battle between the Soviet state and the people of Ukraine was not only about food but also faith. As it always is with communism. Communists not only deny God but hate God. “Communism begins where atheism begins,” said Karl Marx. Bolshevik leader Nikolai Bukharin stated: “We must fight religion at the tip of the spear.”

They fought the religious with the spear, with the gun, with the axe, with the noose, with anything at their disposal.

The communists demanded full obedience not to any Church but to the state, to the gospel of Marx and Lenin. One Ukrainian citizen, Olena Doviskaya, told me: “Everywhere you went, there were statues everywhere of Lenin. They wanted you to worship Lenin.” Of course, many of the faithful refused to do any such thing, and in return were punished severely.

Quite fittingly, when Pope John Paul II visited the Ukraine in June 2001, 10 years after the people broke free from the clutches of the USSR, he invoked not the names of great politicians or monarchs or philosophers but the “saints and martyrs of this land,” beginning with John the Baptist:

“Look today to John the Baptist, an enduring model of fidelity to God and his Law,” urged the Slavic pope to these fellow Slavs. “John prepared the way for Christ by the testimony of his word and his life. Imitate him with docile and trusting generosity…. He is a model of uprightness and courage in defending the truth, for which he was prepared to pay in his person, even to the point of imprisonment and death.”

The Holy Father referred to the Ukraine as the land “drenched with the blood of martyrs,” and implored the people to learn from “the school of Christ, in the footsteps of Saint John the Baptist.”

There were many Ukrainian religious and lay people who fought the Moscow beast and did what they could to defend the faith and stand for their God. They were individuals like Bishop Vasyl Velychkovsky, Father Severian Baranyk, Father Zenobius Kovalyk, Cardinal Josyf Slipyj, Nicholas Charnetsky, Blessed Olympia Bida, Josyp Terelya, and so many more. Many of the countless martyrs truly are known only to the heavens. These individuals were heroes of the faith. They modeled penance and mortification and virtue and holiness and the interior life, conforming to the will not of an atheistic regime but Divine Providence in service of God and neighbor.

Each of these individuals is a story unto himself, but for here, I’ll offer just a few words on one of them:

Bishop Vasyl Velychkovsky (1903-73), a Redemptorist, has been called a “saint for religious liberty.” His story is powerful, tragic, and unfortunately, not unusual for those persecuted by communists. After hounding him for months in the closing days of World War II, with the bishop going from village to village to attend to his flock, the Soviets got their hands on Velychkovsky on August 7, 1945 in the monastery in the village of Ternopil. His crime: spreading “anti-Soviet propaganda.”

They demanded that he deny his faith. He refused. They then demanded that he abandon the Roman Catholic Church and instead join the Russian Orthodox Church, which the communists had been aggressively infiltrating and seeking to take over. Stalin hoped to establish in Moscow a state-controlled church that could challenge the supremacy of the Roman Catholic Church and the bishop of Rome. (See my chapter on this in my book, The Devil and Karl Marx.) Here again, Velychkovsky refused: “You can shoot and kill me,” he shrugged. He would be punished, brutally, unrelentingly.

For a full year, Velychkovsky was housed in a cell at a KGB prison in Kiev, the capital of the Ukraine. Ironically, this began for him a lifelong prison ministry that he would continue (as an intercessor) into death. It also began a life of torture. He was interrogated, beaten, and drugged—the standard treatment. The same was being done to priests and bishops and cardinals throughout Eastern Europe behind the Iron Curtain (Josef Mindszenty is a famous example). Again, the bishop held firm. For clinging to his faith, he was ordered to be executed by firing squad.

For the communists, however, killing the priest was too easy. That would merely send him to his God. Instead, they sent him to one of the coldest prison camps in all of Siberia. When that didn’t crush the bishop, they transported him to an even harsher prison in Moscow. That didn’t break him either.

The communists were hellbent on physically, emotionally, mentally, and, above all, spiritually annihilating Velychkovsky. They did not relent. And the bishop never gave in. He ultimately died in prison on June 30, 1973. He was not an old man, having just turned 70, but physically, he might as well have been 100 years old. He had been destroyed. But his soul was not destroyed.

Velychkovsky was beatified by Pope John Paul II on June 27, 2001, along with a bunch of other martyrs from the Ukrainian Catholic Church. Today his remains are enshrined at St. Joseph’s Ukrainian Catholic Church in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. He has also been proclaimed a patron of prison ministry by the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Of course, persecution continued through the very end of the Soviet Union, in Ukraine and elsewhere. Even under Mikhail Gorbachev’s improvements under his glasnost, repression was ongoing. President Ronald Reagan himself saw this during his May-June 1988 trip to the Soviet Union. In fact, even during Reagan’s stay in Moscow there were troubling signs. The Los Angeles Times reported amid Reagan’s stay that KGB security police dragged five Ukrainian Catholics from a Moscow-bound train in order to prevent them from meeting with Reagan during his visit.

Again, it continued.

Regrettably, peace does not govern relations between the Ukrainian people and Russia today. They look across their long border at the cold face of Vladimir Putin, who during the 1980s was beginning his career as a lieutenant colonel in the KGB. He is today’s Russian strongman. He is poised to invade the Ukraine again today, as his army did in 2014. This time, he would seize even more territory.

Once again, the Church and its faithful look upward for help. Once again, they are on their knees, many of them joining the call of Pope Francis for a national day of prayer for peace in their country.

As they do, names like Vasyl Velychkovsky, Severian Baranyk, Zenobius Kovalyk, Josyf Slipyj, Nicholas Charnetsky, Blessed Olympia Bida, and Josyp Terelya are like ghosts from the pasts, not unlike the forgotten faces of the millions who perished in those fields in the 1930s. But they are more than that. They are examples of heroic virtue and holiness to inspire us all, inside and outside the land of martyrs known as Ukraine.